Widening the Search for the Missing Victims of ISIS: Idlib and Aleppo

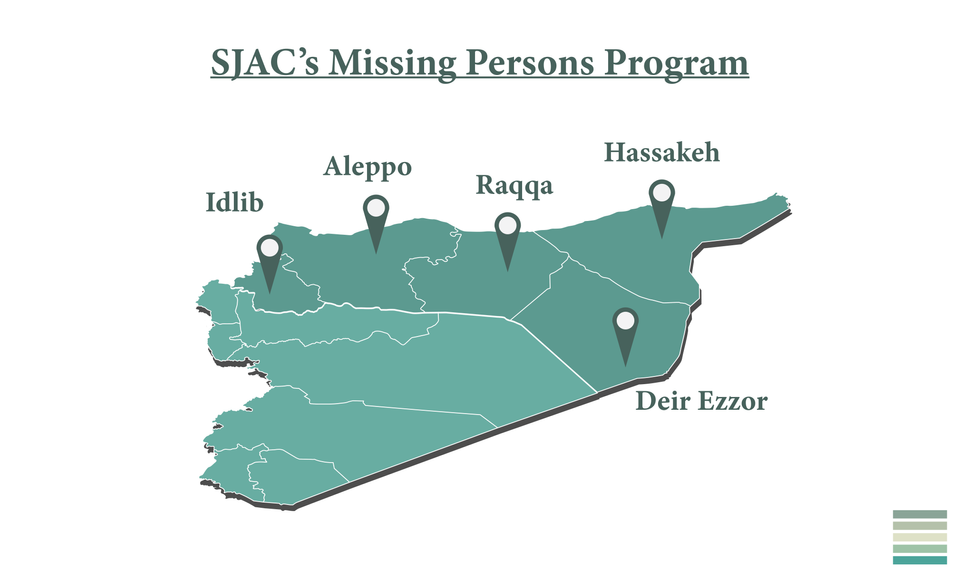

SJAC has recently expanded the geographic scope of its missing persons program to include formerly ISIS-controlled areas of Idlib and Aleppo governorates. Although SJAC has previously documented cases of forced disappearance at the hands of ISIS in these areas—in addition to its ongoing work in Raqqa, Deir Ezzor, and Hassakeh governorates—this documentation often stemmed from investigations into specific ISIS perpetrators. However, SJAC is now actively looking to document cases of forced disappearance that occurred around different areas of Idlib and Aleppo governorates during the period of ISIS control. Documenting in these areas marks another step in the search for the missing victims of ISIS, while bringing new opportunities and challenges.

SJAC decided to expand its missing persons program into Idlib and Aleppo to fill a geographic gap in its documentation, and because doing so will enhance its search efforts throughout formerly ISIS-controlled Syria. Local authorities in these areas, as elsewhere in Syria, have failed to assist Syrian families in their search for missing loved ones. SJAC aims to address this problem by interviewing families about the circumstances in which their loved ones disappeared and developing theories about their fates and whereabouts based on the documentation it has already collected from hundreds of other family interviews, internal ISIS documents, satellite imagery, and open-source information. SJAC is eager to learn from these families as well as survivors of ISIS detention and insider witnesses about the nature of forced disappearance in northwest Syria. This will contribute to SJAC’s growing understanding of the ISIS detention apparatus, allowing it to determine the relationship between new detention facilities and grave sites so as to narrow the possible fates and whereabouts of those who disappeared in Idlib and Aleppo. Given that as ISIS lost territory in northwest Syria in late 2013 and early 2014 and subsequently moved detainees from this area into the northeast, knowledge about who the organization had initially detained in Aleppo and Idlib will help clarify the identities of those whom it was still holding in Raqqa and other ISIS strongholds in the northeast.

The duration and nature of the ISIS presence in Idlib and Aleppo, which was defined by volatile battlefield dynamics rather than relatively stable political control, may have led to distinct patterns of disappearance. Although the timeline of the spread of ISIS is complex and nonlinear, it is clear that the organization maintained a presence across much of northeast Syria between the middle of 2013 and late 2017. It was only between roughly early 2013 and early 2014, however, that ISIS operated extensively across the northwest.[1] ISIS was pushed out of Idlib and Aleppo City by June 2014, with the city of al-Bab marking the approximate western border of its control until approximately February 2017.

In the face of sustained armed opposition in the northwest, between 2014 and 2017 ISIS increasingly focused on consolidating control in Raqqa, Deir Ezzor, and Hassakeh governorates and the territory it had seized in Iraq. Indeed, while ISIS was able to establish a long-term judicial and security apparatus in northeast Syria, in the northwest it was mostly preoccupied with immediate military clashes with other salafi-jihadi groups like Jabhat al-Nusra and armed opposition factions in general. The fluctuating military context in which ISIS operated in the northwest, particularly in Idlib, meant that those whom ISIS detained and disappeared in 2013-2014 were likely more often armed combatants than civilians. Although ISIS of course targeted members of the civilian opposition wherever it operated, the organization may have arrested civilians in fewer numbers in the northwest given that it was already in a vulnerable military position and sought to avoid alienating the civilian population in this earlier period of its development. This would stand in contrast to places like Raqqa, where the ISIS security apparatus grew to include both morality and regular police forces which arrested hundreds if not thousands of civilians for a variety of reasons and over a period of several years.

SJAC’s initial documentation efforts in the northwest suggest that the profile of ISIS detainees here was indeed distinct. For example, SJAC documentation coordinators covering this area have spoken with one survivor of ISIS detention who was held in a facility near Aleppo City and saw that it was populated almost entirely with captive fighters from the Free Syrian Army (FSA). ISIS reportedly executed most of these FSA fighters at the facility itself after declaring them apostates, as it would later do against many civilian detainees living under its control. SJAC must collect much more documentation from the northwest before it is possible to develop theories about the fate and whereabouts of large numbers of people who went missing during the period of ISIS control.

There are several major challenges to documentation efforts in the northwest, some of which are unique to conditions in this part of the country. First, the relatively short period of time in which ISIS was a major party to the conflict in northwest Syria, along with the rapid turnover in political control over the area, makes it more difficult to establish the circumstances and likely perpetrators involved in cases of forced disappearance. In 2013 it was often difficult to distinguish between ISIS and other salafi-jihadi groups like Jabhat al-Nusra, for example, due to the shifting allegiances of their affiliates. Second, the continued political instability in northwest Syria makes it more difficult to safely conduct interviews than in the northeast, especially with another Turkish military offensive in the area imminent. Finally, building trust with families of the missing, survivors of ISIS detention, and insider witnesses continues to be a challenge across formerly ISIS-controlled Syria. The fear of retribution by ISIS sleeper cells is universal, while in Idlib specifically families express concern that the local governing authorities tied to what was once Jabhat al-Nusra will accuse them of being ISIS supporters themselves.

Despite these challenges, it is imperative to continue expanding the geographic scope of the search for the missing victims of ISIS. If you have a loved one who is missing from formerly ISIS-controlled parts of Idlib and Aleppo or any other area of Syria and would like to document their case with SJAC, please contact us at [email protected].

[1] For a detailed account of ISIS during this period, see Charles Lister, The Syrian Jihad: Al-Qaeda, the Islamic State and the Evolution of an Insurgency (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015), pp. 119-218.