Perpetrators’ documentation as sources for casualty recording

[Previously published on Every Casualty on October 20, 2021]

This article is based on the presentation given by Roger Lu Phillips at a webinar on casualty recording in Syria, on 21 September 2021.

Roger Lu Phillips is Legal Director at the Syrian Justice and Accountability Centre (SJAC), where he oversees teams documenting and analysing evidence of atrocity crimes. He leads SJAC’s partnerships with various UN investigative entities and special war crimes units prosecuting Syrian war crimes under the principle of universal jurisdiction. Previously, Roger served as a UN legal officer at the Khmer Rouge Tribunal and the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda.

The Syrian Justice and Accountability Centre (SJAC) aims to support transitional justice and accountability processes, by documenting evidence of human rights violations, war crimes, and casualties in the Syrian conflict. Despite the many limitations that currently exist to successful casualty recording in Syria, there are steps which can be taken now to contribute to the eventual compilation of comprehensive, verifiable casualty records in future.

Despite their lack of transparency or willing cooperation with casualty recorders and international investigators, the Syrian authorities and other parties to the conflict are themselves a valuable source of information on casualties. When they can be obtained, the records and documents produced by these actors for internal purposes can provide vital corroborative evidence. This repurposing of perpetrators’ records to support investigative and accountability processes is not unique to Syria, and has been used successfully in other conflict (or post-conflict) contexts, including Cambodia.

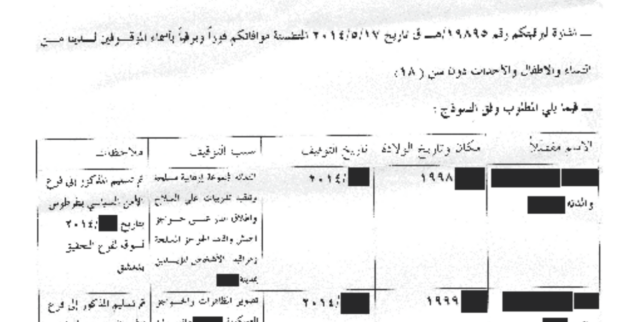

SJAC has been able to obtain government documents from intelligence facilities when they were evacuated during the conflict.[1] One such document [shown below] is a communication from the political security branch in Idlib to Damascus. It lists the names of a number of women and minors (redacted here for security reasons) who have been detained, where they are being held, and the reasons, often spurious, for their detention. This kind of specific, verifiable information is extremely useful and can be cross checked against witness informants.

Syrian government detainee list

In another context, in northeast Syria, SJAC was able to obtain documents produced by ISIS.[2] These documents mimic the trappings of a government, often copying Syrian government styles, and include headers, signatures and stamps. One example [shown here] is an arrest record and judgement against a particular defendant, who was sentenced to death for blasphemy. As the document includes the defendant’s name, it can be used to determine the individual’s fate and contribute to a casualty record. The information in this type of document can and should be cross checked against statements of eyewitnesses to the execution (which ISIS often conducts publicly).

ISIS judgment

Although useful, these types of document are not comprehensive. The Syrian government, which is the single biggest perpetrator of crimes against civilians in Syria, has not been sharing information with NGO and UN investigators. In order to develop a comprehensive casualty list, the cooperation of the government is essential.

Similar documentation has been used in Cambodia for purposes of accountability, prosecutions, and memorialisation of the victims of the 1975 – 1979 Khmer Rouge government. One of the specific tasks undertaken by the UN hybrid tribunal was to identify the victims killed at the Tuol Sleng prison in Phnom Penh. The investigating judges had staff specifically dedicated to creating a searchable database of victims. Despite the fact the conflict ended more than forty years ago, much of the evidence used for this purpose comes from contemporaneous sources including prison logs with lists and photographs of detainees, written confessions, government communications and witness interviews. These sources were compiled to create a searchable database.

After the Vietnamese invasion of Cambodia which overturned the rule of the Khmer Rouge government, investigators found large numbers of photographs of detainees at Tuol Sleng prison. These often included the detainee’s name written on the back. They also found other records, including prisoner lists and a logbook recording how many detainees entered the prison at a particular time, where they came from, and how many were released or died in prison. Those who were ‘released’ were usually sent to the Choeung Ek killing fields to be executed. The prisoner lists included each detainees’ name, occupation, and date of arrival at the prison. Together, these sources provide both qualitative and quantitative casualty data. They also reveal where the Khmer Rouge was conducting internal purges at particular times.

Prison logbook, Cambodia, courtesy of Roger Phillips

There were hundreds of prisoner lists and these were sometimes repetitive. This meant it was important to cross-check and de-duplicate the information they contained. There is also no accepted transliteration of names from Khmer to English, which can cause difficulties in identifying individuals. This is an important reminder that even when detailed, concrete information is available directly from government sources, it must be processed carefully.

Investigators also found useful documentation in the form of prisoners’ confessions. These are often torture-tainted so they are of limited value for prosecution purposes. However, they are a useful source of corroborating evidence for casualty records as they indicate that a specific named prisoner was alive on the date of the interrogation. They can also signal further individuals at risk of detention and execution, due to being named as ‘traitors of the regime’ in a prisoner’s confession.

For the Khmer Rouge hybrid tribunal, the primary purpose of documenting casualties was to support prosecutions. Ultimately, those accused at the tribunal were convicted for the killings of tens of thousands of individuals, based in part on the laborious process of examining all the evidence and documentation cited above. For the families of the missing, the tribunal’s database provided a means to determine the fate of their loved ones by using search filters to identify individuals from the limited information available.

The same information was also used for the purposes of memorialisation of the victims. Tuol Sleng prison remains a museum to what happened during the Khmer Rouge regime and a memorial to those who died there. A selection of the original prisoner photographs continues to be displayed here, with the rest contained in archives in Cambodia. The information was also used to create a memorial stupa, as well as a marble engraving of the names of those who died. These initiatives are an important way to remember the dead and the crimes that were committed against them, as well as to bring closure to families who lost their loved ones in the conflict.

[1] See the SJAC report, Walls Have Ears, for more analysis of Syrian security sector documents.

[2] These documents are included and discussed in SJAC’s report, Judge, Jury and Executioner.

______________________________________________________

For more information or to provide feedback, please contact SJAC at [email protected] and follow us on Facebook and Twitter. Subscribe to SJAC’s newsletter for updates on our work.