Verified Evidence Reveals Rights Violations in Suwayda

On July 13, 2025, the Internal Security Forces of the Syrian government halted traffic on the Damascus-Suwayda road after a Druze truck driver was reportedly kidnapped, an action that was swiftly met with retaliatory attacks. By the evening of July 13, the violence had escalated, and tens of individuals were already reported to have been killed as General Security forces were deployed on the administrative borders of Suwayda. Within the next 24 hours, what started as localized clashes quickly evolved as Israel launched raids targeting different villages while the Syrian Ministry of Defense simultaneously began entering various towns in the governorate. After the collapse of the ceasefire, Arab tribal leadership in Syria announced their armed campaign against Suwayda to protect Bedouin families residing around the governate. It is estimated that over tens of thousands of fighters attacked Suwayda for the next three days, and it is likely that hundreds of civilians were killed, although the Syria Justice and Accountability Centre (SJAC) has not independently verified these accounts. Since then, a regionally brokered and internationally sponsored ceasefire agreement seems to be holding, but scores of Bedouin families have been forcibly displaced as part of the deal.

Details and testimonies from the events in Suwayda are still being revealed and investigated, and verification remains difficult due to the internet blackout imposed on the province and survivors’ fears of speaking out. Complicating the issue is the vast amount of misinformation circulated online, particularly from individuals outside Syria stoking further violence. Despite these difficulties, SJAC has analyzed the evidence of some of the most egregious rights violations that occurred in Suwayda and reiterates the need for justice and accountability processes that are inclusive of all segments of Syrian society as means to prevent future violence.

Context

The city of Suwayda, also the capital of the Suwayda Governorate, is located in Southern Syria near the Jordanian border. The majority of individuals living in Suwayda belong to the Druze community, while thousands of Bedouin communities also live on the outskirts of the city. Leaders from the community have been in contact with the Syrian government since the fall of Assad to establish what kind of relationship the community will have with the new government. For instance, in February, President Ahmed al-Sharaa met with Druze dignitaries, reaching a memorandum of understanding in March.

However, violence again erupted in July. During the concentrated period of violence in July, a wide array of videos and images were shared online that documented serious human rights violations carried out against the Syrian people in Suwayda and included information about potential perpetrators. Although not a comprehensive overview of the events that occurred, the rights violations included in this article provide additional insight into the events that unfolded and the nature and scope of the violations that occurred.

Rights Violations Documented in July Clashes

After analyzing open-source data, SJAC has identified numerous war crimes that occurred in the concentrated period of violence in Suwayda in July. Notably, Common Article 3 of the Geneva Conventions prohibits the following acts in non-international armed conflict: (1) violence to life and person, in particular murder, cruel treatment and torture; (2) taking of hostages; (3) outrages on personal dignity, in particular humiliating and degrading treatment; and (4) the carrying out of executions without previous judgement pronounced by a regularly constituted court (i.e. extrajudicial killings). For this report, SJAC has documented evidence of each of these violations during the height of the violence in Suwayda. These acts, if proven, also constitute domestic crimes per the Syrian law.

Extrajudicial killings

First, SJAC analyzed open-source documentation that confirms civilians were summarily killed, including one instance in which three related individuals were simultaneously executed: brothers Moath Bashar Arnous and Baraa Bashar Arnous, in addition to their cousin Osama Modad Arnous (photo, left to right). The footage is available online and has circulated widely, including on Facebook, and the location of the incident was geolocated by the Verify platform (منصة تأكد) at coordinates 32°42'45.33"N, 36°33'53.45"E. This geolocation supports the identification of Suwayda as the location of the crime and reinforces the credibility of the footage documenting the execution.

The video documenting the crime shows the three men—one visibly bleeding—being led to a balcony in a multi-story building, where they are surrounded by several armed men who order them to jump. As the victims hesitate to comply with the order to jump off the ledge, the perpetrators begin shouting at them and insulting them with obscene language. Just as the three individuals move toward the edge, the armed men open fire, shooting them before they jump. The victims were later identified by a friend of their cousin, who also reported that the father of Moath and Baraa, Bashar Arnous, was found dead near the entrance of the house. Such acts constitute the domestic crime of murder as well as the war crime of extrajudicial killings.

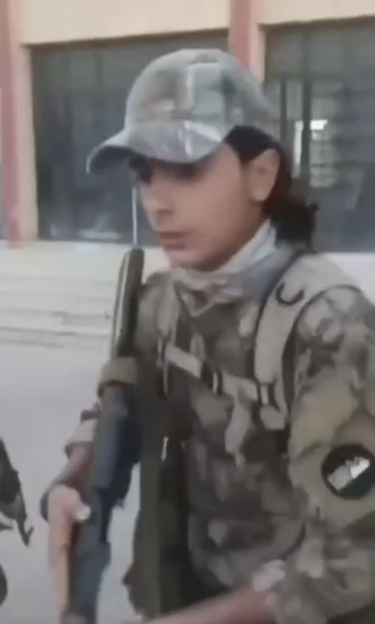

At least four of the perpetrators were dressed in camouflage without any visible insignia, while others wore civilian clothes. The absence of identifying marks on the uniforms is a troubling pattern seen frequently across Syria, raising serious concerns about accountability and the deliberate concealment of affiliation by armed actors, as the practice of wearing unmarked attire may signal malicious intent and an effort to evade identification or prosecution.

In other cases, SJAC verified that individuals were executed only after the perpetrator confirmed the sect of the victim. For example, one execution documented on video shows an unarmed man seated on the ground, surrounded by armed men who question him aggressively about his religious identity—specifically asking whether he is Muslim or Druze. The man initially responds by saying he is Syrian, but the response only appears to frustrate his interrogators. One of the perpetrators presses further, asking, “What do you mean by Syrian? Are you Muslim or Druze?” As the man hesitates, a voice off-camera repeatedly asserts that the man sitting is Druze. Eventually, when one of the gunmen asks directly, “Are you Druze or not?” The man replies, “Brother, I am Druze.” He is immediately shot dead.

The victim was later identified as Monir Ar-Rajmeh.

Visual evidence suggests the execution took place in the yard of a school building, as indicated by the design of the stairs, entrance, windows, and other architectural features typical of school facilities in Syria. At one point, the camera pans to show a view of the street and neighboring buildings outside the school. Based on this footage, the location has been verified as the Martyr Mohammad Saleh Nasr School (مدرسة الشهيد محمد صالح نصر) in the village of Al-Thaala, at coordinates 32°42'42.08" N, 36°27'13.09" E.

Unlike the previous incident, where several of the perpetrators appeared in matching unmarked camouflage, the armed men in this case were wearing visibly different types of camouflage, indicating a potential lack of uniformity and organization. In addition, none of the men bore insignia, and notably, one perpetrator’s face is clearly visible in the video.

This should aid efforts by the authorities to identify him and his accomplices and to hold them accountable for what constitutes an extrajudicial killing.

Use of hostages

In addition to extrajudicial killings, SJAC also documented perpetrators detaining individuals as hostages. For example, one video documents an incident in the village of Umm al-Zaytoun (أم الزيتون) in the Suwayda countryside, where Druze fighters appear to be using Bedouin civilians as hostages. The footage shows several Bedouin men seated as the Druze man films them, declaring that he will send the video to their relatives. The cameraman states that they are in Umm al-Zaytoun.

After providing the Bedouin men with assurances of their safety and protection, the cameraman undermines these assurances for the women and children, telling them that if their relatives come to Umm al Zaytoun, “It will not end well. This is not just a threat. This is a threat and something we will do...we will protect you, but if they arrive, you and they will be treated the same.”

Visual details in the footage, alongside verbal references, allowed for the confirmation of the incident’s location at 32°54'24.17" N, 36°35'54.24" E in Umm al-Zaytoun. The situation captured on camera raises serious concerns about the unlawful use of civilians as hostages and threats directed at protected persons.

Cruel, Inhuman, and Degrading Treatment

Lastly, a recurring violation documented in multiple videos relates to the forced shaving of the mustaches of Druze men, an act clearly intended to humiliate members of the Druze community. Among the Druze community, the mustache is deeply tied to cultural and religious identity and is seen as a symbol of manhood and honor, and for religious men, as a sign of dignity and respect.

One such video shows armed men forcibly shaving the mustache of an elderly man, who according to open sources was identified as Murhej Haeil Shaheen from the village of Al-Thaalah. While shaving him, the perpetrators question him about the location of weapons, and the man swears that he has none.

In several other videos, the perpetrators, identified as Sheikh Abu Musab along with another man nicknamed Abo Obaida, are seen using an electric shaving machine to shave the mustaches of elderly and young Druze men. In one clip, an elderly man tries to reason with Abu Musab before his mustache is shaved but is eventually forced to comply. Abu Musab then shaves another man’s mustache, saying mockingly: “These are the mustaches of Bani Ma‘rouf,” using the name the Druze community uses to refer to themselves—demonstrating the intent to target members of the Druze community. In another video, Sheikh Abu Musab appears alongside individuals including Abu Obaida and others, shaving the mustaches of additional men while laughing.

In one case, Abu Musab and the other perpetrators forcibly shaved the mustache of a Red Crescent worker. During the incident, Sheikh Abu Musab tells the worker, “We will not do anything to you for the sake of the old woman,” referring to an elderly woman who stood silently nearby. He then adds, “We will only shave your mustache,” and begins doing so. When the armed men again mockingly refer to the act as removing “the mustaches of Bani Ma‘rouf,” the Red Crescent worker replies, “But I am not from Bani Ma‘rouf,” prompting the cameraman to order him to shut up.

These videos, which are only a small sample, provide evidence of a systematic pattern of abuse that specifically targets the dignity and cultural identity of Druze men. The forced shaving of mustaches—especially of elders and humanitarian workers—is not only degrading but are also intended to send a message of subjugation and ridicule.

Inadequate Transitional Justice Processes Exacerbate Violence

Part of the ongoing rights violations and violence that have erupted in Syria since the fall of Assad is caused by a consistent lack of transparency around transitional justice processes that could address questions of accountability, amnesty, and reconciliation, preventing future violence. For example, the fact-finding committee for the coastal investigation has yet to release its report detailing its findings from the events in March, impacting the level of trust communities have in the government. As such, while President Al-Sharaa emphasized in his speech the importance of achieving justice, protecting minorities, and holding all violators accountable after the events in Suwayda, many Syrians remain skeptical about the government’s ability and willingness to investigate and prosecute those accused of committing violations.

The government has a responsibility to protect Syrian citizens by addressing past violations and preventing their reoccurrence. To meet this responsibility going forward, the Syrian government must launch an investigation into the violence that occurred in Suwayda by all parties—including any perpetrators associated with the Syrian government. The Syrian government should then refer perpetrators to public and impartial trials and pursue a genuine national dialogue inclusive of all segments of Syrian society. Simultaneously, the Syrian government should also allow an independent monitor, such as the UN Commission of Inquiry, to unconditionally enter Suwayda for the purposes of documenting the events in July. Delaying these demands and failing to address the patterns of violence in Syria will only lead to more violence and further delegitimize the Syrian government.

___________________________

For more information or to provide feedback, please contact SJAC at [email protected] and follow us on Facebook and Twitter. Subscribe to SJAC’s newsletter for updates on our work