Documents Obtained by SJAC Show Role of Syrian Intelligence in Directing Humanitarian Aid

In recent weeks, two reports published by Human Rights Watch and Chatham House have shed light on how the Syrian government has effectively ‘co-opted’ the multi-billion-dollar humanitarian relief effort in Syria. Through political pressure and regulations, the government manipulates the flow of humanitarian aid to punish perceived enemy populations, and benefit government loyalists. Insights from these recent reports have largely relied on the perspective of aid workers, who have had to operate with a lack of clarity and information.

To gain a better understanding of the Syrian government’s policy and decision-making processes in regards to humanitarian aid, SJAC searched its database of Syrian government documents for relevant letters and memos. The documents identified outline how Syrian intelligence agencies, the perpetrators of some of the worst human rights abuses throughout the conflict, are playing a central role in directing and monitoring humanitarian aid efforts in Syria.

‘Hot Zones’ vs Safe Zones

Since the start of the conflict, the Syrian government has required international aid organizations to seek government approval for all projects and aid deliveries within Syria. Aid workers interviewed by HRW reported that the majority of requests by international organizations are either denied or ignored with little explanation.

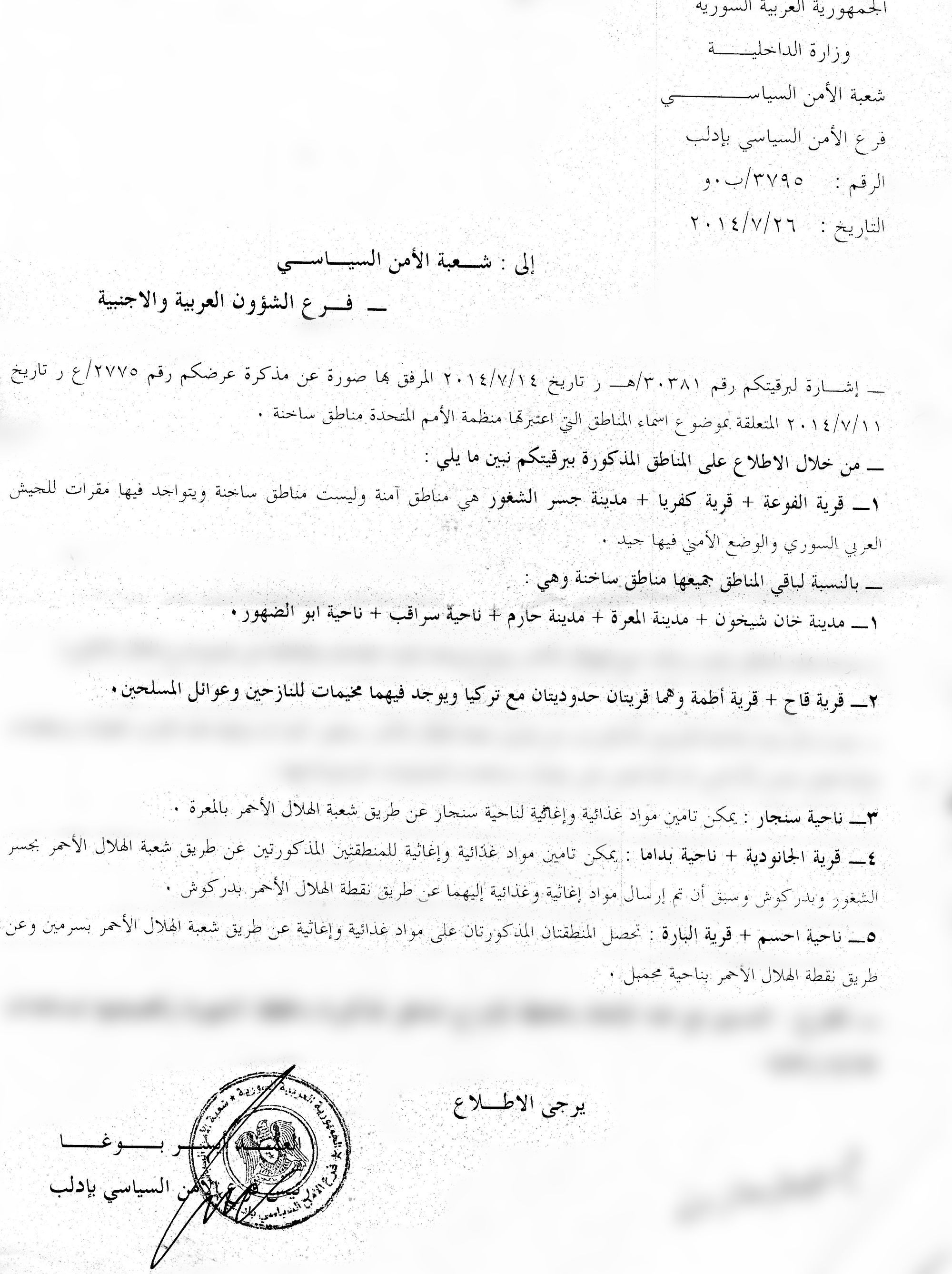

In July 2014, one memo issued by the Political Security Branch of Idlib Governorate shows how the government internally delineates between areas ‘safe’ for aid deliveries and ‘hot zones’ where aid is to be restricted. The document, addressed to the Arab and Foreign Affairs Branch, lists a number of areas where aid agencies have requested access. The city of Jisr Ash-Shughur and the towns of al-Fu’ah and Kafriya are labeled “safe” because “there are military bases there and the security situation is good.” Meanwhile, the towns of Atme and Qah are designated ‘hot zones’ because they contained “families of armed groups and camps for the displaced” (both are the location of large IDP camps).

The explanations here clearly show that access was being determined based on political considerations rather than humanitarian need. Through such restrictions, the government punishes civilian populations perceived to be aligned with the opposition by diverting aid from opposition-held areas and nearby IDP camps, to areas perceived as loyal to the Syrian government.

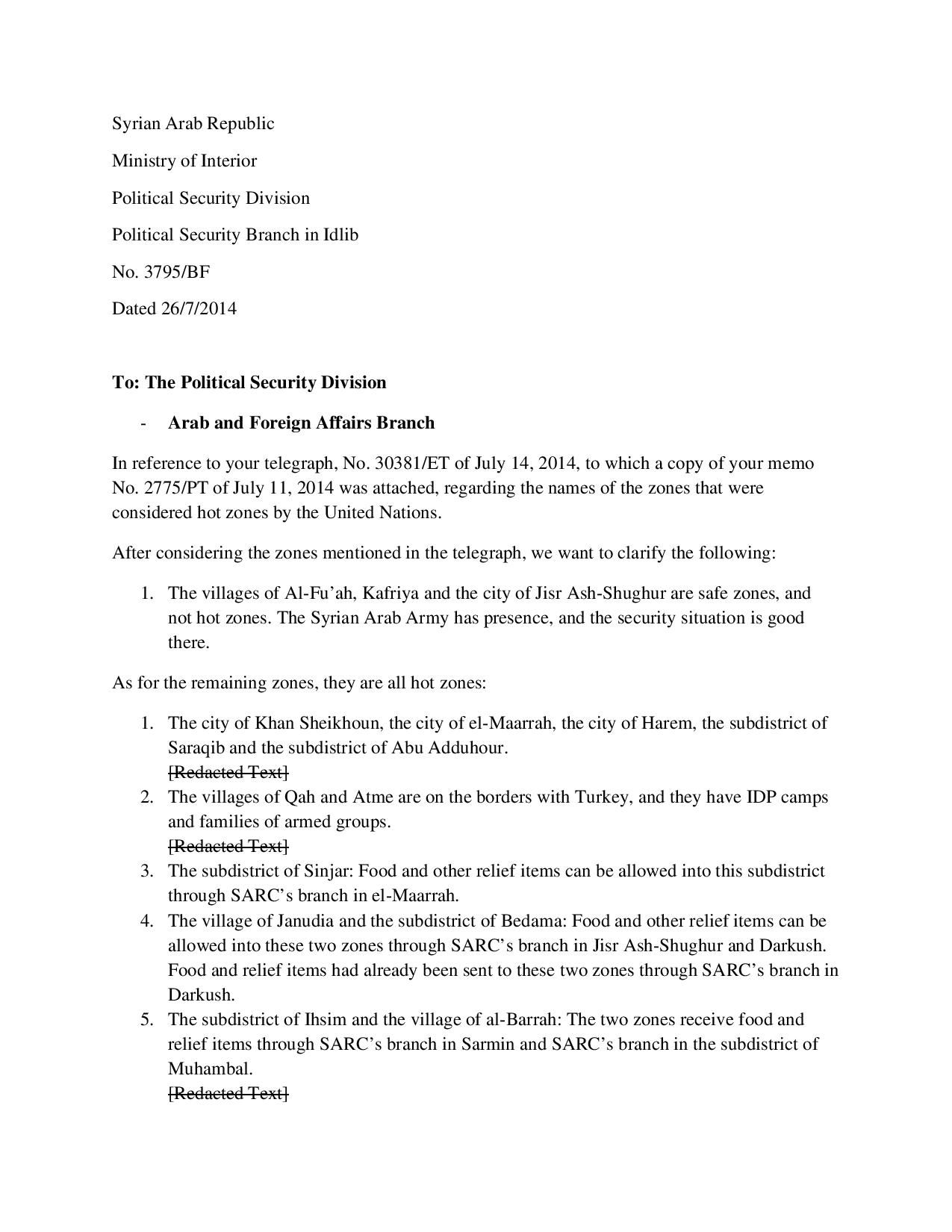

Document A: ‘Safe Areas’ and ‘Hot Zones’

“A Political Decision”

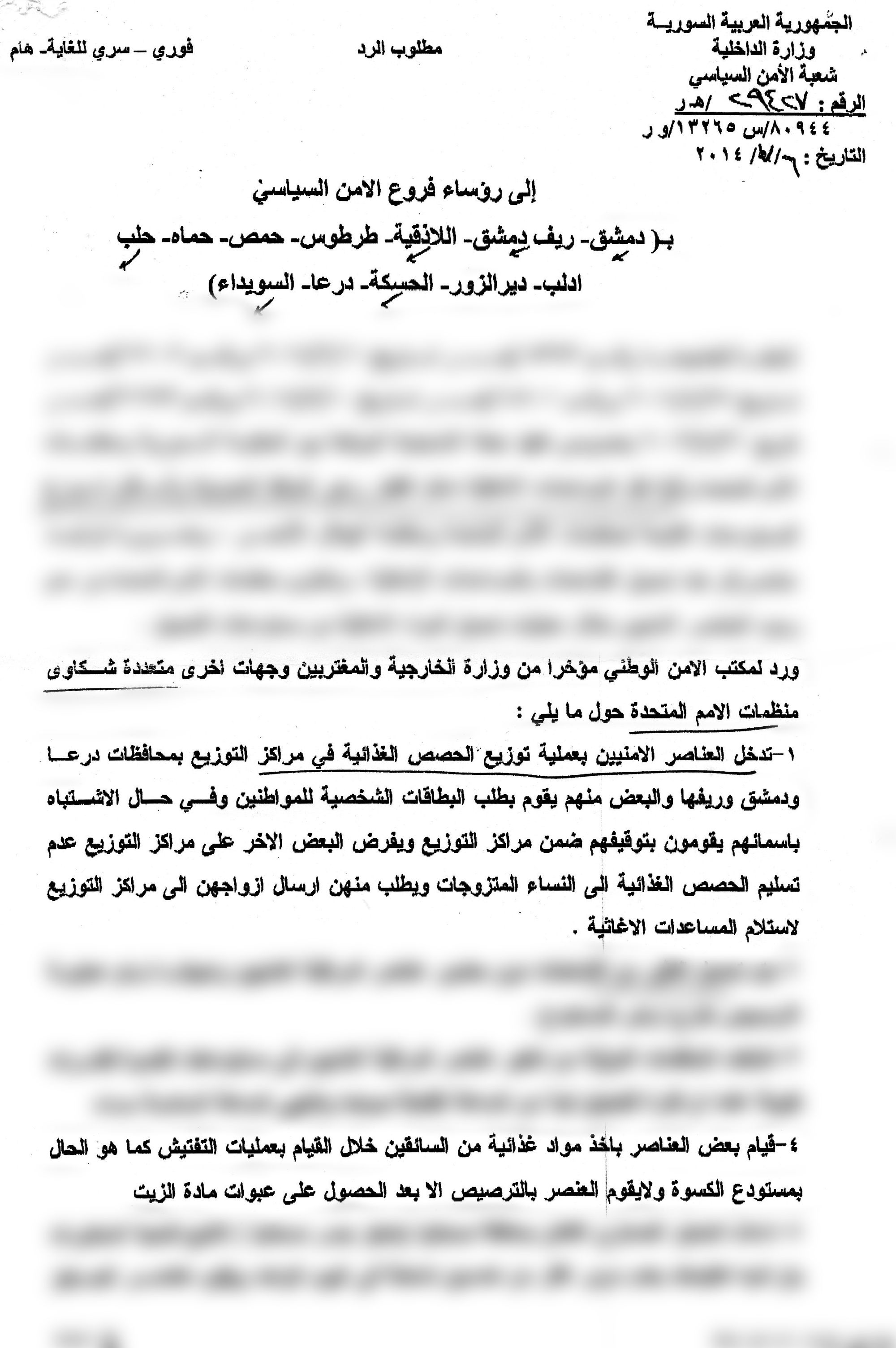

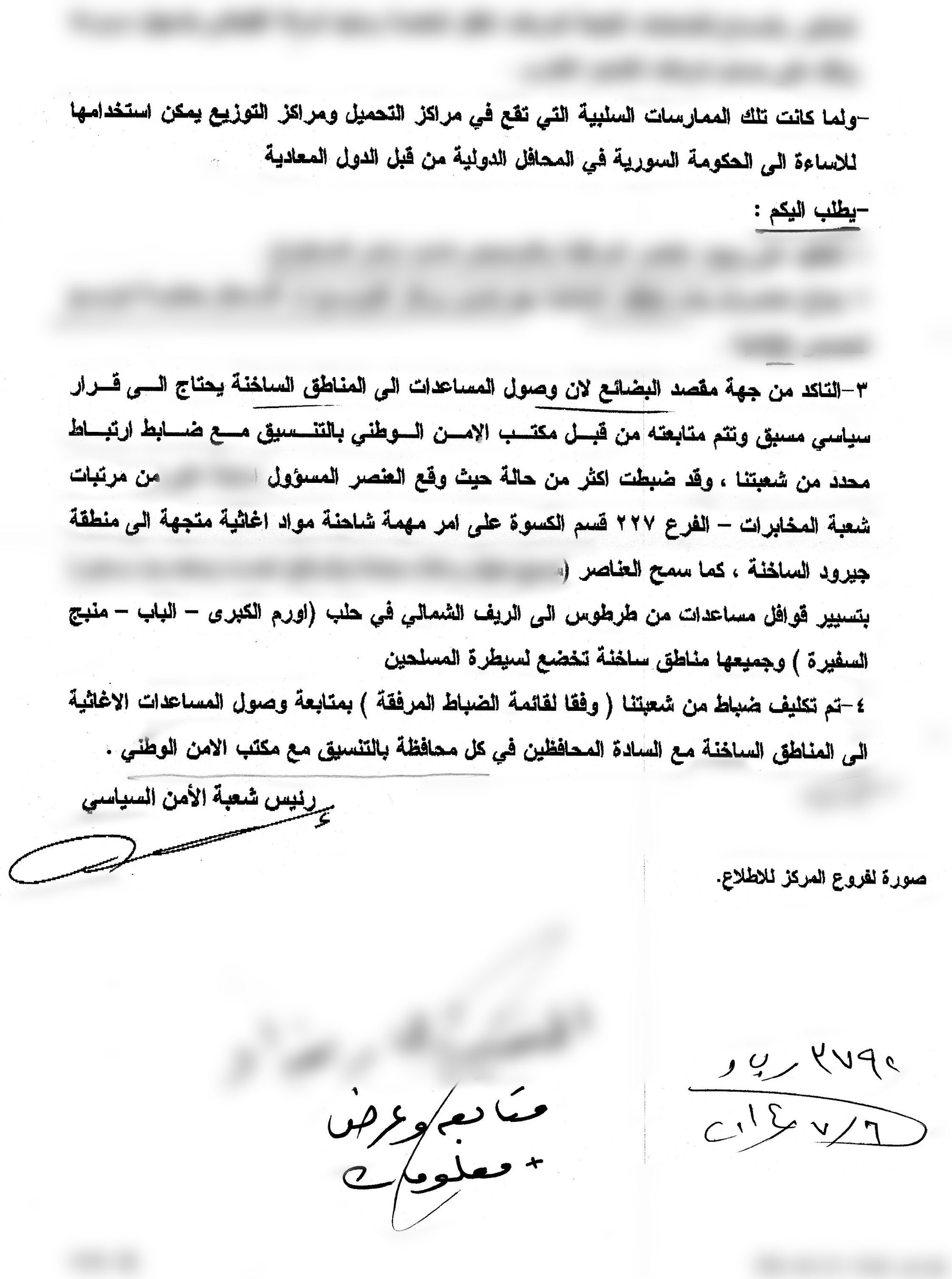

Internal communications also provide clear evidence that the manipulation of aid flows was official policy at the highest levels of government. In July 2014, the Political Security Division of Syrian Intelligence issued a telegram addressed to the heads of its branches in all governates. In the letter, it orders the branches to “check the destination of the aid before dispatch, because the shipment to ‘hot zones’ requires a political decision and is monitored by the National Security office in coordination with the liaison officers from the Political Security Division.” [emphasis added]

The document goes on to name specific officers who have, “without permission,” allowed shipments of humanitarian aid to areas “controlled by the armed groups”. To prevent further mistakes, the letter states that a number of officers from the Political Security Divisions were assigned to monitor and supervise deliveries of humanitarian aid in ‘hot zones’ in coordination with local governors. The fate of the officers reprimanded here is unclear, but in other cases, the government has tried individuals on terrorism charges for distributing humanitarian aid in opposition areas, under the sweeping counter-terrorism law of 2013.

Document B: ‘A Political Decision’

Restrictions on Medical Aid

In particular, the Syrian government has sought to limit the delivery of medical aid to opposition-held areas as a means of denying medical relief to rebel fighters. Another memo issued by the Political Security Division in February 2014 indicates there were official bans on medical aid to opposition-held areas. While stating that security forces may “loosen restrictions that disallowed medical aid to enter hot zones”, it urges officers to “keep in mind the existence of make-shift hospitals that get foreign support and treat armed groups.” This latter qualification implicitly gives officers wide discretion to deny medical aid to any areas where opposition fighters may be present.

The same document also emphasizes that branches should coordinate with the Syrian Red Crescent “to regulate distribution of medical aid to these areas and select the types of aid that will be allowed.” Such instructions underline a common practice in the conflict, whereby the government has forced the removal of medical supplies from aid convoys, often to areas where medicine is most critically needed. In 2018, for example, the government ordered international agencies to strip 70% of medical supplies from a large aid convoy before it could travel to Eastern Ghouta, where the siege had just been lifted after five years.

Syrian government memos obtained by SJAC show how intelligence agencies were giving explicit orders for its branches to work in close coordination with SARC to “regulate the distribution of medical aid to these areas [under opposition control] and select the types of aid that will be allowed.”

Other accusations

In addition, the documents analyzed by SJAC include references to grave allegations made by international aid agencies which have not previously been made public. One telegram notes a letter by the National Security Office outlining a list of complaints from the United Nations and other international humanitarian organizations (IHOs), including allegations that Syrian security forces have seized supplies and arrested aid recipients at distribution centers. In other instances, security forces were allegedly withholding food rations to married women and asking them to send their husbands in their place—likely to find and detain men under their suspicion.

Steps towards accountability

As the documents highlighted here show, international organizations have submitted to a framework that is fundamentally politicized and directed by sectors of the Syrian government that have egregiously violated human rights. In doing so, international aid agencies are inevitably sacrificing their principles of neutrality and impartiality.

In response to recent criticisms, Amin Awad, the director of the MENA bureau at UNHCR responded by stating: “for us, it is secondary who is who. I do not have a mechanism where we comb every single contract [to examine] connection with the regime.” It is true that humanitarian organizations must operate with practicality to provide life-saving aid under extremely restrictive circumstances, but there are feasible steps which agencies could take to improve the current situation. In their reports, HRW and Chatham House offer a number of recommendations, including the creation of a comprehensive monitoring system that will document the reach of aid and ensure compliance to human rights and humanitarian principles.

More fundamentally, organizations and their donors have to start pushing back against the government’s corruption of international aid. The billions of dollars they have poured into Syria have provided a lifeline to the Syrian government. Donors and international aid organizations should utilize this leverage to bolster their independence moving forward.

_____________________

For more information or to provide feedback, please contact SJAC at [email protected] and follow us on Facebook and Twitter.