Strengthening, not Abandoning, the Human Rights Council

Last month the United States officially withdrew from the UN Human Rights Council (UNHRC), calling the Council a “protector of human rights abusers and a cesspool of political bias.” Although few would argue that reforms are not needed, blanket criticisms of the UNHRC disregard that the Council has provided one of the only spaces for direct engagement between human rights defenders and the UN, and that over the past seven years the Council has consistently shone a light on atrocities committed in Syria, while the Security Council has been mired in political deadlock. Member states should continue their efforts to empower the UNHRC by strengthening its relationship with civil society and ensuring that its work is better linked to that of the General Assembly and Security Council.

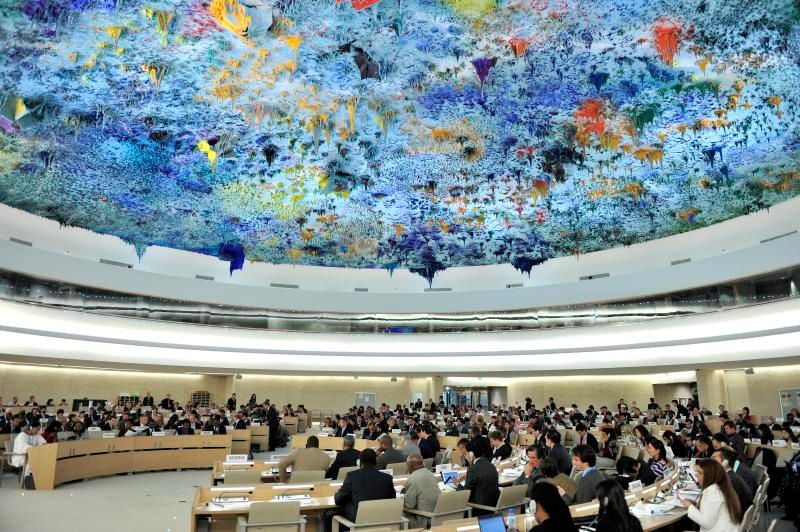

The Human Rights Council was first created in 2006 with the mandate to protect and preserve human rights. The Council has a number of avenues through which to pursue this mandate, including by establishing special procedures (such as commissions of inquiry) to investigate cases of human rights violations and hosting the Universal Periodic Review (UPR) to assess the human rights record of all UN member states every 4.5 years. Despite its successes, the Council also has a number of shortcomings, which other experts have covered thoroughly in more comprehensive reports. For this article, SJAC will focus on two specific areas in need of reform that are of particular importance to Syria.

Civil Society Engagement: Civil society participation, particularly during the Universal Periodic Review and through the complaint procedure, is a cornerstone of the Council’s work. While the UN headquarters in New York is rarely interested in meaningful civil society engagement, the Council has consistently created space for human rights defenders. Not only does this engagement inform the Council’s work, but it enables civil society to foster professional networks and provides opportunities for capacity building, advocacy, and funding. However, there is a barrier to entry for many groups and activists. Lesser known but important civil society organizations often do not have an entrance point to the Council unless they are connected through a middleman, usually a larger, international human rights organizations. Additionally, human rights activists have consistently experienced reprisals for their cooperation with the Council, such as the infamous arrest of Egyptian human rights defender Ebrahim Metwally en route to Geneva. The Council should work directly with the General Assembly to ensure that those who engage with the UN, in any capacity, are protected from retribution in their home country. Although the Council has previously proposed the appointment of a senior official to act as a focal point to respond to reprisals, such efforts have been blocked by the General Assembly. The Council and member states must take more concerted action to revive this effort and ensure the safety of human rights defenders whose efforts are integral to the Council’s work.

Isolation of Human Rights: At the Human Rights Council’s creation, the UN reaffirmed that peace and security, development, and human rights are closely linked, and one cannot be achieved without the others. Yet, the Council, based in Geneva, has historically been cordoned off from the political activities in New York City, where there are greater opportunities for action at the Security Council and General Assembly. As a result, the Council has been unable to effectively mainstream human rights concerns, as has been apparent in its efforts on Syria. Just months after the start of the conflict, the Council created the Commission of Inquiry (COI) for Syria, and over the last seven years it has regularly provided briefings and published in-depth reports on human rights violations. Although the Council has emphasized the Commission’s work through regular hearings, these findings have not translated into policy changes at the Security Council. In fact, political discussions at the UN are often in direct opposition to the findings of the COI, as SJAC has previously noted. COI briefings to the Security Council are provided only at the request of Security Council members and are generally held according to the Arria-Formula, meaning they not formal sessions and do not require the attendance of all members. Regular, on the record briefings, both by the Council at large and by individual special procedures, would ensure that the vital investigative work being done in Geneva reaches those most able to act upon it. Most importantly, it would reaffirm the centrality of human rights to the work of the Security Council.

The work being doing by the Commission of Inquiry and the Human Rights Council at large keeps Syria at the forefront of the global conscience. The United States should not have allowed its concerns with the Council’s work to overshadow the important role of the UNHRC in promoting human rights globally. As a member of both the Human Rights Council and the Security Council, the US could have used its position to address the Council’s challenges. However, as the US rescinded this position, other states must fill the void and rededicate themselves to reforming and strengthening the UNHRC. While there are a host of improvements that can and should be made to the Council’s work, ensuring that civil society has access to the Council, and that the work of the Council is being heard at the General Assembly and Security Council are vital to both improving the quality of the Council’s work, and increasing the chance that it has a real-world impact.

For more information or to provide feedback, please contact SJAC at [email protected].