On the way to work, a trip to death.

The Syria Justice and Accountability Center works to collect and document cases from different sources concerning the arrests and abductions of Syrian citizens. The center is highlighting some of these cases to demonstrate the systematic nature of these actions, to illustrate the center’s work, and to encourage other victims to testify, given the importance of testimony to any future justice and accountability processes in Syria.

This is the testimony of a former Syrian detainee at one of the Intelligence branches, who was kidnapped at a Syrian government checkpoint in Qatifa, Damascus. The prisoner discusses his abduction, the means by which he was tortured, his observations during his detention, and how he was released.

A.T. is 26 years old. He has Syrian citizenship and works in Lebanon. He was heading to Damascus, heading from there to Beirut when the bus he was travelling in was intercepted by security at a checkpoint in Qatifa, Damascus.

AT recalls: “[Authorities] stopped the bus, took passengers’ identity cards, and, a half hour later, asked me to get off the bus. Then, they took my things and forced me to press my thumb on a paper; I did not know the [paper’s] content, except a word I read at the top of the page: terrorist.”

Next, A.T. was transferred to prison in Homs and then transferred to the Mezzeh airport. He recalls this period: “They asked me about my brothers, my father, and the fighters and my relationship with them. I answered that it had nothing to do with me [the fighters had no relationship to me], because I work in Lebanon, and do not know what is going on in Syria. After being tortured and lashed by an electric cable on my skin, I told them that my brothers and my father were fighters. Then they took me inside a room, about 3X3 meters, and in it were four detainees.”

“They repeatedly interrogated me—two or three times a day with the same degree of torture. After each interrogation, they took me to a different room with different detainees. This continued for four days. Then they transferred me to Almantiqu Intelligence branch in Mezzeh.”

Almantiqu Intelligence branch in Mezzeh is one of the places in Syria where detainees are subject to the most torture. The place is best known for the high number of dead bodies that come out of it in a day. A.T. says of his detention here: “They put me in a 4X5 meter room, crammed with about 100 detainees, all completely naked. There, security agents beat detainees with hoses and sticks, deliberately causing head injury. Among those detained were children around 12 or 13 years old and many seniors around 60-70 years old.”

Concerning disease outbreaks among the detainees, A.T. reports: “In Almantiqu Intelligence branch prison, strange disease symptoms appeared—detainees would get blisters on their skin, which then burrowed into their bones and began to emit pus. After 10-15 days, the patient would die.”

“There were detainees who were there for more than two years. [Dead] bodies of detainees accumulated among us and remained for several days—[the security forces] waited until there were 10 bodies or more so they could remove them all at once.”

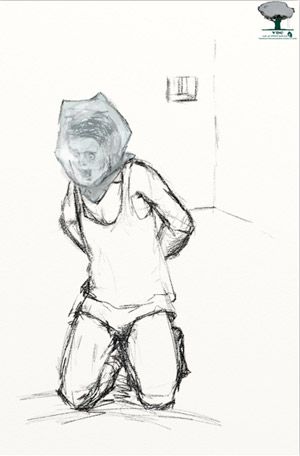

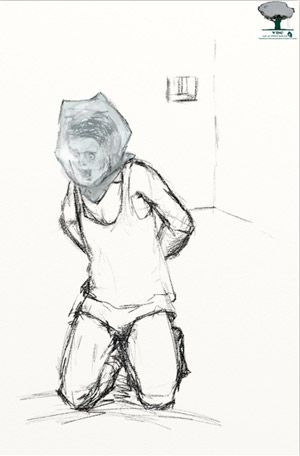

A.T. recalls torture in Almantiqu Intelligence branch: “They interrogated me there and told me, under torture, what I was expected to admit. I was electrocuted and beaten with sticks; [they] used tools of torture whose names I do not know. They tied my hands behind my back, flipped me facedown, put a chair between my body and arms, and then flipped me again until my head dropped to my feet. And then they restricted my breathing severely and asked me if I recognized what they told me. Then they sprinkled water on me and beat me with electric sticks. And when I admitted to whatever they wanted, they pressed my thumb (fingerprint) on a piece of paper while I was blindfolded.”

After the interrogation ended, A.T. was sent to a military security branch where he stayed for around 45 days. A.T. says of this period: “I was exposed to less torture in the military security branch. They hit me in the beginning, and then put me in a room with other detainees, where we had to urinate and defecate, because there was no possibility of leaving the room to go to the toilet. I spent 15 days there, and then they put me in solitary confinement after making me (again) press my thumb on a new confession stating that I am a deserter from compulsory military service.”

“A 30-year-old prison guard there told me they would not beat me anymore, but it was unclear when my trial would be. He also said that my file needed some support and he can do that for me for 300 thousand Syrian Pounds [approximately 2,000 USD]. When I approved he allowed me to contact my brother in Lebanon and ask him to transfer the amount to the company ‘Pyramid Exchange’ in Damascus. The next day he took me to the company’s office and they received the payment. He then took me to a new, clean room. The next morning, I was transferred to the Court of Terrorism in the Justice Palace in Damascus, where I was released and given all of my belongings that were with me when I was arrested.”

International human rights law prohibits kidnapping and torture in ordinary times as well as during times of violent conflict.

The above account draws attention to the relationship between the citizen and the judiciary. Transitional justice relies upon citizens’ confidence in their judiciaries. In Syria, judicial institutions must undergo meaningful reform to gain the trust of citizens, which, in turn, can pave the way for transitional justice efforts.