Inside the Raslan Trial #18: The Czech and a Journalist: “the corpse’s head knocked against each step”

TRIAL OF ANWAR RASLAN and EYAD AL GHARIB

Higher Regional Court – Koblenz, Germany

Trial Monitoring Report 18

Hearing Dates: November 17, 18 & 19, 2020

CAUTION: Some testimony includes descriptions of torture.

Summaries/Highlights:[1]

Trial Day 43 – November 17, 2020

Christopher Engels from the Commission for International Justice and Accountability (CIJA) testified as an expert before the Court. He explained that CIJA has collected evidence of crimes committed by parties in the Syrian conflict to use at future international criminal investigations. The material includes testimony from seven witnesses who confirmed that Anwar Raslan was the head of the Interrogation Unit at Branch 251 - “the most effective, dangerous, and secretive Branch.” Engels explained how CIJA acquires, corroborates, and preserves evidence, as well as the organization’s involvement with the trial in Koblenz.

Trial Day 44 – November 18, 2020

On the second day of Christopher Engels’ testimony, he discussed two reports compiled by CIJA pertaining to Anwar Raslan. Throughout the reports, which were requested by German authorities, Raslan was referred to by a codename: the Czech. Engels elaborated on the CIJA’s preparation of the reports, and also explained the hierarchy of Branches under the Syrian government.

The Court announced that the trial against Eyad would be separated on Feb. 17 with a final verdict to be delivered on Feb. 24.

Trial Day 45 – November 19, 2020

The witness, P19, was a 43-year-old female journalist from Damascus. She helped organize demonstrations across the city. As a result, she was detained in various security Branches, including Branch 251. The witness recounted the night when security forces stormed her family’s home, found medications she planned to send to activists in Homs, then detained her and her siblings. She described how security personnel perpetrated sexual violence against women, and told the court about the methods of torture she witnessed which resulted in the death of other detainees.

Day 43 of Trial – November 17, 2020

Bessler appeared for Reiger. Mrs. Köhler was the German-English translator. Scharmer asked if the witness could have headphones to hear better. Kerber said that the headphones were for Arabic translation, but Arabic translation was not provided during this session.

The proceedings began after 9:00AM. There were around five spectators and two individuals from the media in the audience.

Testimony of Christopher Engels

The witness was 45-year-old Christopher Engels who works for the Commission for International Justice and Accountability (CIJA), an NGO that collects evidence from conflict zones for future international criminal law investigations. Questions were posed in German and the witness testified in English.

Note from the Court Monitor: Translation inaccuracies were discussed several times.

Judge Kerber’s Questioning

Kerber asked Engels if he worked for CIJA. Engels confirmed and noted that he works in the Netherlands.

Kerber asked Engels if he was related to either of the accused by blood or marriage. Engels said no.

Kerber noted that Engels sent a PowerPoint to the Court, then asked Engels to tell the Court about his background. Engels explained that he is an American lawyer who studied in the United States and has two master degrees. He acquired international experience in the Balkans where he worked with international and local experts to establish a court in Bosnia and Herzegovina to deal with war crimes. This was a big step for international criminal law. Prior to that, he dealt with tribunals in Bosnia and Herzegovina and in the Hague. However, when they built a court in Bosnia and Herzegovina, he decided to stay there before they gave it to local lawyers. Afterward, he became an advisor on war crimes and was engaged in different regions. For example, he worked as an advisor in Afghanistan with Afghani legal teams, as well as in south-east Asia and in Iraq.

Kerber asked Engels about CIJA. Engels asked if he could use the PowerPoint [which he started using]. Engels explained that he had been working with CIJA for six years as the Director of Investigations and Director of Operations, and he oversees the work at CIJA. CIJA began working in 2011 on issues pertaining to the situation in Syria and the Syrian regime. It was established as an NGO because it saw a gap in international criminal law investigations: The most important evidence is collected after a conflict, not during it because there is no court of law. The goal was to fill that gap since evidence was either lost or people disappeared. They worked with Syrian colleagues and collected evidence that could be important.

Kerber asked if CIJA began to work in 2011. Engels confirmed it was toward the end of 2011.

Wiedner asked if [the work undertaken in the beginning of CIJA] was also regarding Syria. Engels confirmed and noted that to accomplish this goal, CIJA worked with Syrian colleagues and provided them with its expertise, then made sure to hold the information until needed. They thought that it would be a short-term project (maybe a year) then give the information to a court. Unfortunately, that did not happen. Since 2011, CIJA has collected material and has interviewed people. The original thinking changed from working with an international court to domestic courts. It conducted investigations related to Syria and court procedures. It allied with other authorities related to criminal procedures. Some European agencies started to ask CIJA about information it had. The purpose was to support international justice and, on a smaller scale, to support investigations and so, they did it gladly. Later, they became proactive and prepared a document whenever they heard about a person in Europe or North America.

Scharmer corrected the translation and said that he did not contact the person. Instead, he filed a dossier about this person.

Wiedner asked if those dossiers were about people who came into consideration as possible suspects. Engels confirmed, pointed to the PowerPoint and explained that CIJA has a detailed scope of work. The primary focus is collecting material. The second focus is interviewing witnesses. The third focus is collecting secondary material. CIJA has more than 800,000 documents from the Syrian regime (mostly from the intelligence services and the Syrian military) that CIJA smuggled out of Syria. When the material was outside of Syria, it was scanned, copied and stored. CIJA worked on the digital copies not to harm the original versions and to make the work efficient. It was important to them to answer to others, so a key point was to make the material searchable (for names, locations, etc). Engels said that CIJA wanted to preserve material so it was not lost, but was also [securely protected]. He explained that when one party leaves a conflict area, CIJA’s people enter it and collect evidence. They package the material and move it to a safe location. They do not review the material there. They package it and securely move it elsewhere before they can get it outside of Syria. When the opportunity arises (it may take days or a year) to get the material outside Syria, it is brought out of the country. Then they scan the documents and store the originals in archive boxes. Each page is barcoded and examined afterwards by an analyst. No assessment is done about which documents belong together (e.g., if five pages belong to the same document). They do not make assumptions, which is important to preserve the work. Generally, that is how they handle the material. They also have other means of collecting evidence that are used less often: (1) collecting documents from a person with knowledge (e.g., if a person was there and left, then CIJA collected it), (2) interviewing people who handed over the material, and (3) an electronic format through electronic devices like laptops (but none of the material regarding the trial was collected that way) or electronic devices on which someone else collected material, then CIJA acquires the device, scans it, and gives back the devices (no material regarding the trial was collected this way).

Kerber asked if the documents were given barcodes. Engels confirmed that the documents were given barcodes and numbers. Every translation has the same number. CIJA conducted more than 2,500 interviews with witnesses, including: eyewitnesses, former regime members and victims (over 1,000 detainees). CIJA saw the need to speak with witnesses. The problem was that they often talked to a witness years after an incident occurred. CIJA is an NGO and not a government. Anyone working for CIJA has experience in the past with international organs and governments. CIJA does not write down the statements from witnesses word-for-word. Instead witnesses told stories to CIJA who accepted the information as a third party. The reason why CIJA was involved was so that witnesses can be helpful in several ways. First, documents showed information that was supported by the information from interviews. Second, information from witnesses helped fill the gap in evidence. Third, witnesses gave background information about the conflict. Some drew images of where and how the crimes happened which was important information for colleagues who were investigating. Finding witnesses is the key purpose of their work, because the vast majority are still in Syria which means that they do not have access to European authorities and their voices are not heard at all. Law enforcement authorities are not available to speak directly with witnesses during a conflict.

Kerber asked if CIJA informs witnesses of their rights or if it is simply a conversation between two persons privately. Engels confirmed that CIJA has a protocol for speaking to witnesses. CIJA staff members participate in mentor programs and are trained on how to speak with witnesses. The focus is whether the information is sensitive and not to ask leading questions. They explain to witnesses who CIJA is and why they are speaking to them. They say clearly that the witnesses’ information may be used, then ask if they have any security concerns or if they talked to others. They guarantee that witness names will not be used without approval, otherwise names are redacted. If anyone wants to speak with a witness (e.g., prosecution authorities), CIJA asks why. CIJA noticed that there was tension between the court and the witness. For example, an investigator might tell the witness to testify in the Hague and when it does not happen, the witness loses faith in justice.

Wiedner asked if the documents of the witnesses were all anonymized due to security concerns or because witnesses did not approve. Engels confirmed and explained that open-source material would not be part of today’s presentation. In this part, he wanted to attempt to clarify the structure of the military and other intelligence services, like political security and the Air Force Intelligence Services. It is important to understand that the main bodies are responsible and coordinate with each other. Engels expanded on the following:

1. National Security Bureau (governmental authority): Head of the single panels. Highest level panel regarding the coordination of intelligence services.

2. Central Crisis Management Cell: Ad-hoc panel that includes everyone from number 1 and other ministries. It was established to manage the crisis. Afterwards, it became the highest-level security body. First document was from March 2011 and the last from July 2012, which was the main period CIJA focused on. It was established by Al-Assad and informs decisions. It dictates the policy for other procedures.

3. Security committees in the regional governorates.

Kroker highlighted a mistake in the translation: “governorate” does not mean “government” but “province”. Engels said that one can use “governorate” or “province” and that each governorate has their own security organizations.

Engels said that this slide was a summary. It showed how the collection of information escalated quickly in April 2011. The regime started using language like “the time for tolerance is over” and “use force against them.” On August 05, 2011, the regime ordered more arrests and the use of the paramilitaries to control the situation.

Wiedner asked if CIJA had the relevant documents. Engels confirmed. He did not have the originals with him. They are archived. He only had copies. All of the scans have a number at the top left corner with “Et” (English translation). There is a barcode. Under the barcode is the number and the English translation. On the slide, the key point was the first highlighted line that said “18 April 2011” and “CCMC”. The top left said “military intelligence.” The document was exclusively for the head of the Branches. It said (1) “Time for tolerance is over. Time to use all means of weapons,” (2) “Confrontation with demonstrators as follows: No release of detainees.” There was also a point to train selected personnel to use weapons. Civilian party members were included. At the end of the document, there was the signature of the head of the military intelligence services, and a directive that the message should be sent to all Branches. It was indeed sent to all authorities in the country.

Wiedner asked if “party members” refers to the Al-Ba'th Party. Engels confirmed. He pointed to a slide on the PowerPoint which had a snapshot of the document from CCMC that was from April 20, 2011 and conatined the phrases “new stage to fight conspiracy”, “use of force”, “orders to make plans”, and “in coordination with the military apparatus.”

Wiedner asked from where Engels got the document. Engels said that he would talk about it later.

Judge Kerber asked if Engels has hard copies of the document. Engels confirmed that he has hard copies of all the documents that are included in the slides. The first document was from April 18 [no year mentioned] and was collected in March 2015 from the office of the military intelligence in Idlib. In 2016, it was transported from Syria to Turkey. In March 2016, a colleague personally handed it over to the team. On May 23, CIJA received it among a collection of boxes. They had six boxes of material from the same day and location.

Wiedner asked if they took the original as a paper from the office. Engels confirmed.

Klinge asked if Engels has more information about the person who collected the six boxes. Engels said that the person who collected the boxes cooperated with CIJA for years. He was a Syrian and was at that location, which is why he had access to the office. He was responsible for handing the box to someone else in Syria.

Klinge asked if the person worked with the regime intelligence services or if he was there coincidentally. Engels said the person was only able to access the office after the regime left Idlib.

Wiedner asked about the document dated April 20, 2011. Engels said that the document is from the bundle (box number = SY.P013).

Wiedner asked if it was brought out of Syria the same way. P said yes, as part of the same bundle.

Kerber asked if Engels wanted a break. Engels said yes, after 10 minutes. Engels continued that “new phase, engagement of the army” lays out the idea that the regime was responsible for the detention. A document from August 5, 2011 from the National Security Bureau was sent to the security committees in the provinces and shows how the Bureau says that they should engage in collective security campaigns and on whom to focus, then defines what they see as the problem (generally, opposition of the regime). Here, it specifies the targets: people who finance the demonstrations, members of the coordinating committees, people with communication abroad and foreign media. The documents say what to do after getting control by joint committees and that the National Security Bureau should be informed.

Wiedner asked how it entered their possession. Engels said that it was collected in Ar-Raqqa at the military security detachment in Tal Abyad [تل أبيض] directly from the intelligence office, then personally carried to the headquarters to be scanned on November 18, 2013.

Wiedner asked if the person was a member of the regime. Engels said no, it was collected after the regime left the location.

Kerber asked if Engels had copies of these three documents with him. Engels confirmed.

***

[20-minute-break]

***

Engels explained that the next slide was a summary of another longer slide. Bigger circles represented CCMC. Smaller circles represented the National Security Bureau.

Judge Kerber read out the document which included the names:

· Mohammad Sa’eed Bekhtyan محمد سعيد بخيتان

· Hasan Turkmani حسن تركماني

· Dawoud Rajha داوود راجحة Minister of Defence

· Mohammad Ash-Sha'aar محمد الشعار Minister of Interior

· Mohammad Deeb Zaytoun محمد ديب زيتون head of political security

· Hisham Bekhtyar هشام بختيار head of the National Security Bureau

· Ali Mamlouk علي مملوك

· Abdelfattah Qodsiyya عبد الفتاح قدسية head of military intelligence

· Jamil Hasan جميل حسن head of the Air Force intelligence

Engels said that [these people were involved in] a chain of messages [that was forwarded] from the National Security Bureau (NSB) to the provinces, and from superiors to their subordinates. The key point here is that the messages were sent down.

Next were examples confirming that the messages were sent from the Branch level to members, starting with the NSB to heads of the Branches, then from the Branches to lower levels. The message said that “you are requested to arrest inciters/financers/who speak with foreign parties/members of coordinating committees.” Wiedner asked from where they got the original. Engels said that this document is from the detachment in Ar-Raqqa.

Next was an example of the response, which came from the head of the Political Security Branch in Ar-Raqqa (with his signature) and was forwarded to his superior. It informed him how the Branch “worked as requested, and arrested inciters and demonstrators.” The [original physical copy of the] document went from the Political Security Branch on April 5, 2013 to Turkey then to CIJA headquarters in March 2014. The original was scanned and archived.

Next, Engels showed a document with the instructions that were given to local-level authorities. For example, interrogators were instructed to ask the following questions: “You have photos in your phone from the demonstration, what did you do there? What was your role? Was it uploaded online? Was it shared with foreign media? Tell us who demonstrated and who incited others? Who are the members of the coordinating committees?” Engels said that the redacted information in the document was because [the detainee] was asked to mention names during the interrogation. The document was collected from the east region from a colleague, then came to CIJA.

[Oehmichen pointed out that the translation of “colleague” was wrong. He asked if “colleague” actually meant “team member.” Engels confirmed. It is from a team member.]

The next slide was an example of a wanted list from the Military Intelligence Service sent to the military commanders. It contained the names of wanted individuals. If someone was wanted, it was because his name was mentioned by someone else during an interrogation. The head of the Intelligence Branch gave instructions for the military commander. The document was handwritten and signed.

Wiedner asked from where Engels got the document. Engels said the document went from Dar’a, to Brigade 38’s headquarters in Sayda [صيدا] then to CIJA (after the regime withdrew from Sayda). Engels mentioned that a witness was detained in the Political Security Branch in Deir ez-Zor and was named in the document. CIJA interviewed 16 witnesses whose names appeared in the documents. CIJA knew the document was a list of detainees because one of the witness’s names appeared there. The document was received from the Political Security Branch in Deir ez-Zor and sent to the headquarters of CIJA. It is still there.

Engels described detention in the Political Security Branch, including the conditions there—solitary cells, no lights, general abuse, abuse during interrogations, forcibly signing and fingerprinting papers without reading them, and transfer to other Branches.

Engels then explained how statements of the witnesses were corroborated with information. In the Caesar photos, there are numbers indicating the Branch where the person was detained. CIJA was able to tie photos to the relevant numbers in four documents. Engels showed an example in which authorities said that the person died from heart failure or respiratory failure. The body had a number indicating that he was in Military Intelligence Branch 227.

Kroker asked about the translation of death certifications. Engels said that this is a report of Military Intelligence Services about the interrogation and death of a person, in addition to a document that certified the death, and a number. But this is not an official death certificate.

Kroker asked if Engels knew of similar documents. Engels confirmed. The origin of that document is the Military Intelligence Services in Idlib. It then went to CIJA headquarters.

Next, was a reference from a Caesar photo was shown.

Then a map was shown that displayed the movement of 200 detainees by the Military Intelligence Services. There is evidence that other intelligence services did the same. The map shows that the witness’s description was consistent with the contents of the document. They were arrested and interrogated locally, and when needed, they were transferred to Damascus. This document also generally mentioned injuries. CIJA talked with 1,000 detainees who revealed that the patterns of abuse by the Intelligence Services were the same across Syria. It is important to clarify the widespread and systematic abuse from different offices [authorities] with the same purpose.

Kerber asked if a lunch break should be issued. Engels said whatever the best for the court.

***

[Lunch break]

***

The next slide was about the General Intelligence Directorate (GID) - Branches 251, 285 and section 40.

The head of GID:

Ali Mamlouk 2006 - 2012 (member of CCMC + NSB)

Mohammad Deeb Zaytoun 2012 - 2019

Hosam Louqa 2019 – Today

Kerber asked if Branch 251 was a regional Branch. Engels said Branch 251 is for Damascus and the surrounding area.

Engels said that CIJA has: 13,000 internal regime documents, around 180 linked interviews, 60 insider interviews, 100 victim interviews. They have around 600 documents that are linked to Branch 251 (showing how the regime’s “opponents” were detained, and describing interrogations and periodic updates). They conducted interviews with 13 former Branch employees. Seven witnesses mentioned Raslan as the head of the Interrogation Unit in Branch 251. Branch 251 was described as the most effective, dangerous, and secretive Branch. It was responsible for Damascus and its surroundings. It has several sections. One of them is the Investigation Section. It has external sections, like the notorious Section 40. Branch 251 is responsible for interrogating detainees, as well as other responsibilities in different regions (e.g., checkpoints, search and raid campaigns, arrests).

Engels showed another example of documents from March 28, 2011 regarding Branch 255. It said, “in case found, kindly arrest the driver and refer him to us alive.” It was signed by the head of GID. Similar requests were issued.

Engels then showed a document from 2012 in which the Military Intelligence Branch in Ar-Raqqa advised on the search for a person, then requested the person is referred to Branch 251. Similarly, another document requested a referral to Branch 285 for the person to be interrogated.

Kerber asked what the goal was for sending someone to Branches 251 or 285. Engels said that both Branches interrogated people who were perceived to be important. 285 is a central Branch with continuing interrogations. 251 is not only geographically allocated to Damascus, but also conducts further interrogations [of detainees transferred] from other Branches. Based on documentation from all over Syria, 251 searched for information and referred to other Branches. For example, if someone was searched for in Idlib, the information was shared by GID to all Branches.

Kerber asked if there is a central organ and a regional one. Engels confirmed. It is important to see that actual decisions were made. In this report, you could see the words: “From the head of Branch 251 to the head of GID… We found no evidence and recommend release… We found evidence against others and transferred to Branch 285.” The document came from GID in late 2016, then went to CIJA in June 2017.

Next, GID/251/Section 40 pertaining to city section of Al-Jisr Al-Abyad جسر الأبيض]]. It has a reputation for being powerful and notorious. It is headed by Hafez Makhlouf [حافظ مخلوف]. Normally, documents come from the head of the Branch, not from the head of the section. Therefore, it is rare to find documents from a section. The head of Section 40 would send information to the head of Military Intelligence Services (which is not usually the case), then to the head of the Branch.

The next document was sent by Branch 251 to the head of military intelligence. At the bottom, the document was signed by the head of Section 40. It had information about future attacks. The document went from Idlib in March 2015 to Branch 271, then to the headquarters in November 2016 where it was scanned.

Wiedner asked if there is information about the responsibilities of Section 40. Engels said that there was no direct evidence, but it was indicated from documents and insider witnesses that Section 40 has special independence. They did not attend all Branch meetings and could act before being given orders. There is “information about [Section 40’s] reputation”. But there is no information about the specific tasks because of the relationship between the head of Section 40 and Al-Assad.

Wiedner asked if Section 40 had their own locations/detention centers. Engels said that because it is a section, there is limited information. The types of abuse performed at Section 40 included: beating with sticks and cables; tied to chair/flying carpet and beaten; suspended in Shabh and beaten; fingerprints and signing papers without reading; death in detention. There are 145 Caesar photos linked to Branch 251. The data is from 2011 – 2012 and focuses on detention in this period.

Wiedner asked if there is information about deaths and what happened to corpses. Engels said no, he did not have information on that.

Klinge asked about a report from July 19, 2018 and quoted “witness reported about a guard called [name redacted] who said that many died from suffocation from overcrowding and were then brought to Harasta [حرستا]. It seemed as if they died in the hospital. They had 50-60 corpses/week that were brought to the mass graves in Najha [نجها] by trucks.” Engels said he confirmed this information from a person whom he interviewed.

Klinge asked about the Shabh torturing method. Engels described it as hanging someone, and there are variations. Sometimes toes touch the floor or sometimes the person is completely hung. People were also hung from their arms during interrogation.

Böcker asked when the conversation with the witness took place. Engels asked if the number was 218. Böcker said yes. Klinge said that was the footnote and provided the number [there was some discussion about the right number and footnotes, and p said eventually:] on March 1, 2018.

Böcker asked if the conversation happened as Engels previously described, and that there was no instruction of rights. Engels confirmed.

Kroker recalled that “detainees who died during detention in 251 were piled up and showed signs of torture. Some were so defaced that their facial features could not be recognized anymore.” Engels thought it was important to explain the difference between two points: [the document referenced] says “death in detention,” but people who CIJA talked with said that they saw corpses in the Branch. Only one witness used that example.

Branch 285 was discussed next. CIJA has approximately 300 documents about the role of this Branch. They received interrogation reports and some detainees were interviewed there. They conducted 12 interviews with insiders who mentioned Branch 285. Three people mentioned Raslan. 16 witnesses were detained there. 285 is a central Branch. It is operational rather than a field Branch. Some of its functions were stated in the documents. Its main purpose is interrogation and referral of detainees from other Branches who are then transferred to military or civil courts. An example was then shown of a document with the signature of the head of the Investigation Unit of Investigation Branch 331 in Idlib. It suggested the transfer of a detainee to Branch 285 to complete the interrogation.

Wiedner asked Engels to tell in his own words which cases were transferred to Branch 285. Engels said that there are two general scenarios: (1) the person was searched by Branch 251 and was transferred to 285 (when someone is wanted, he is sent to Branch 285), and (2) people in the field decide that a person is important enough to be transferred. The document is from the GID Branch Idlib. It was found in 2016, brought to Turkey, then to CIJA headquarters in June 2017.

Next, an investigation report was shown from Branch 285. It was sent to the head of GID. Raslan’s name was in it, in addition to the names of officials. It said “interrogations by conciliation committee.”

On the left side of the next document [in Arabic], Raslan’s name was visible. The name was replicated on the right name of the document. The document was not signed. Two other documents were signed. All had a similar structure. Engels wanted to show these because they corroborated the interview. The two signed documents are from GID in Idlib. The last one was collected from another person. They were found in March 2015 and were handed over to CIJA in 2016.

Next was an example of a person who was interviewed. There was a discrepancy between what the witness said and what was in the document. The witness said that he was detained in Aleppo while he carried a flag and a weapon given to him by his father. But the document said that he sold weapons to armed groups in Aleppo. There was also no mention of abuse in the document, though the witness described how he was abused during interrogation. The methods of abuse that were mentioned included: Shabh, fingerprints, multiple interrogations by that, beating upon arrival, kicking and beating with sticks and whips, tied to chairs/flying carpet, suspended in Shabh; Doulab [tyre] and forced confessions.

The proceedings were adjourned at 2:45PM. The next trial will be November 18, 2020 at 9:30AM.

Trial Day 44 – November 18, 2020

The proceedings began at 9:30AM. There were four spectators and two individuals from the media in the audience.

Continued Testimony of Christopher Engels

Judge Wiedner’s Questioning

Wiedner asked how CIJA prepared its report from July 19, 2018. Engels said that it was compiled in a similar way as other reports. First, information was requested, then CIJA initiated procedures when it had information in which the judiciary was interested. For this specific report, the authorities were interested in Raslan and CIJA had information. CIJA looked at their material and decided what was relevant to the case. They also gathered information from witnesses about the related Branches. The documentation related to Damascus did not actually come from Damascus—the Syrian regime did not leave Damascus; therefore, the information was from other Branches. CIJA took the information and worked with Arabic-speaking analysts. They then made the report for the authorities.

Wiedner asked if Raslan was code-named “Czech.” Engels confirmed.

Wiedner recalled that Engels referred to “insider witnesses” and asked what that means. Engels said CIJA utilized insider witnesses who formerly worked for the regime (CIJA does not engage with individuals who currently work for the regime). Information from insider witnesses was sometimes not supported by documents.

Wiedner asked if there was a chain of hierarchy. Engels confirmed. He explained that the background of the reports describes how there were massive efforts by the regime to arrest members of the opposition throughout Syria who were interrogated in various Branches. Each Branch has its own section responsible for interrogations. Branches 251 and 285 are examples of where interrogations were held.

Wiedner asked if releasing detainees was the decision of the head of the Branch. Engels confirmed that this was the case in Branches across Syria, including Section 40.

Wiedner asked if Engels was speaking of the head of the GID, not about 251 and 285. Engels said that the regional Branches had more independence from the head of the Branch, and they were responsible for giving information and making decisions.

Wiedner asked if there was knowledge about Ali Mamlouk. Engels confirmed.

Wiedner asked if Raslan was ever assigned specific tasks (related to abuse or detention) in the documentation. CIJA found evidence that Raslan was in charge of the interrogation units for Branches 251 and 285. These Branches were responsible for interrogation where abuse was happening, but the documents did not directly assign Raslan these tasks.

Wiedner asked Engels if he remembered his answer to the question of whether Raslan committed abuse. Engels did not remember, so Wiedner recalled Engels’ testimony that “yes, Raslan was the head of the interrogation unit in the Branch where abuse happened.” Wiedner said that he took that answer to mean that there was abuse in the Branch. Engels confirmed.

Wiedner asked about the independence of Section 40. Engels said that, based on information from witnesses and documents, Section 40 had independence, which means that it did not work under normal circumstances.

Wiedner asked if Section 40 was playing the role of the “commando.” Engels said yes, this was relayed by insider witnesses.

Wiedner asked about Section 40’s tasks. Engels said that Section 40 has its own missions – it was somewhat independent and worked alone. It conducted its own interrogations and made release decisions without higher level approval. Members of Section 40 did not attend meetings.

Wiedner recalled Engels’ testimony from the day before that detainees were transferred to Branch 285 when their previous Branch was full. Engels confirmed.

Wiedner pointed to a footnote that said that many people died in Branch 251, and that two witness saw corpses whose faces were unrecognizable in June 2011. [Name redacted] said that in 2012 the cells were overcrowded and corpses were transferred to Harasta حرستا. Detainees died in the cells and they were transferred to Najha نجها during the weekend. Engels confirmed this information.

Prosecutor Klinge’s Questioning

Klinge asked how CIJA was funded. Engels explained that CIJA was funded by (the ministries of foreign affairs of) States interested in these projects. The states include Germany, Canada, US, UK, and the Netherlands. These States do not have influence over CIJA and CIJA does not take money from States who interfere.

Klinge asked about the staff members and their training/education. Engels said that CIJA has approximately 150 staff members, most of whom worked on international justice issues. They have a large diversity of experience. Some are lawyers, analysts, etc. The majority of the staff worked internationally in locations like Yugoslavia, Rwanda, Cambodia, Sierra Leone, and the Balkans. Regarding projects in Arabic-speaking countries, CIJA has team members who studied Arabic and are able to engage directly with the texts. It is hard to translate all the documents. Another group who is the backbone of CIJA’s work is in Syria. They collected the documents and the work would have been impossible without them. Some of them have legal backgrounds, and are lawyers and judges.

Klinge asked if Engels is in contact with them. Engels said that the majority of the contacts were from 2011 – 2012. It is a slow process and they worked with people on the ground. Broad networks are efficient for understanding the process and, as long as they were objective and motivated, it does not matter if they were Syrian or others.

Klinge asked if Engels has contact with other organizations. Engels is in contact with IIIM and the UN Commission of Inquiry.

Klinge asked how CIJA and IIIM cooperated. Engels said that IIIM has asked it to collect information on Syria. CIJA has allowed IIIM to access its database. The Commission of Inquiry is different.

Klinge asked about collecting information regarding Raslan and CIJA’s cooperation with the Federal Criminal Police Office (BKA). Engels said that the one thing he got from all his contacts was that the person is in Europe and CIJA searched if they have information about him.

Klinge said that the prosecution had information from CIJA and asked Engels if CIJA worked on the matter before that. Engels said that the report in which “Czech” was used was done before the request. CIJA continued working on it. When CIJA finished the process, they answered the request about Raslan with the information they had. Raslan was in Germany at this time. This was confirmed by CIJA.

Klinge asked why CIJA used the name “Czech.” Engels explained that one of his colleagues suggested it while they were thinking of a code-name unrelated to Raslan.

Defense’sQuestioning

Böcker asked if CIJA was founded in 2011. Engels confirmed that CIJA started in 2011 in relation to Syria work. The idea came to expand to the world when the organization changed its name in 2012.

Böcker asked if the evidence was secured in 2011 and if the system [of barcodes and number labels] was used from the start. Engels confirmed and added that the basic concept of the system is to collect evidence and store it so it can be used in 10 – 15 years. Evidence management set up the system based on their past experiences.

Böcker asked when Raslan was first referred to as “Czech.” Engels did not know. Böcker recalled Engels’ answer to the police about this question in which Engels said “mid 2017.” Engels said that he could “say with confidence” that his answer was based on documentation.

Böcker noted that Engels said he did not know who “Czech” was in the first version of the report, but that he addressed Raslan by name in the second report. Engels clarified that CIJA produced different drafts because of the updates from the BKA about Raslan. Then they answered with the name of the person the BKA was looking for. Böcker clarified that he was referring to the report from April 13, 2018. Engels said that he wanted to search the reference.

Böcker said that Engels could take a break.

Kerber asked about the number of the report. Böcker said the reports were from July 19, 2018 and April 13, 2018.

***

[15-minute-break]

***

Kerber said that the last question was about the development of the reports. Engels said that there are two version as far as he knew.

Böcker said that he had two versions: one with “Czech” and one with “Raslan.” Engels said that what CIJA has is the original request from December 24, 2017, a draft for the BKA on January 01, and the updated version from April 13. Then they continued their internal work to finish this project on July 19 and maintained the same name. They produced the reports and evaluated them, unlike the request from the BKA.

Böcker asked why they did not simply use “Raslan.” Engels said that he could say that the report from July 19, 2018 is the final product.

Böcker said that the report from April 13 was changed. He asked Engels about the States that finance CIJA and if Qatar was one of them. Engels said Qatar is not one of them.

Fratzki asked if the documents were lost and found in other locations. Engels said that the documents were not collected until the regime left the location.

Fratzki asked if Engels’ staff found the document in the building. Engels confirmed. Some of CIJA’s colleagues went to the location and took the documents. In general, there are other documents CIJA received from insiders who took the documents with them when they left Syria, but those documents were not part of this presentation. Documents were not collected from Damascus. In the early days of the conflict, CIJA had to explain to the opposition that the documents were important for future cases, so CIJA cooperated with them. This is what CIJA had to do to go inside the buildings.

Linke asked if Russia also funded CIJA. Engels said no.

Schuster asked if the information about GID was provided by insiders who worked with the regime. Engels said that CIJA corroborated documents through insiders and witnesses. There is not a formula for corroboration. But if they take a document from an insider, it holds the same value.

Schuster asked about witness protection and if insiders have concerns about testifying. Engels said that CIJA asks, during the witness interview, if the person has security concerns. Because CIJA does not offer witness protection, they only speak with people who do not have security concerns. The trust of the witness is taken seriously. Names are not shared.

Schuster asked if insider witnesses had concerns. Engels said yes, there was a fear of reprisal from the Syrian regime and sometimes concerns for the witness’ family if he is from the opposition. But the dynamics changed enormously. Some witnesses were happy to talk in 2011 – 2013, but now they have concerns. So, “we” ask them again if they have concerns before publishing the information.

Schuster asked about insiders. Engels said the majority who left the regime left in 2012 – 2013 (general statement). Very few have left the regime over the last two years. Engels thought this was because: (1) many people already left (2) some people thought that “the regime is now winning, so there is no point to leave now.”

Schuster asked about the consequences of leaving the regime. Engels said it is clear that the regime is sending messages to people who seek out the opposition and who might be suspects. A document from a high-ranking official said that if people do not do their job, then they should be reported.

Schuster asked Engels why he laughed when Böcker asked whether Qatar funded CIJA. Engels explained that he laughed because Qatar finances other projects, not theirs.

Plaintiffs’ Counsel Questioning

Schulz asked if there is transparency about who funds which project. Engels said that he did not know about public relations with the donors.

Schulz asked which projects Germany is funding. Engels said that Germany funded the discussion today. More specifically, Germany provided support for the technical elements, like scanning and copying material.

Schulz noted Engels’ testimony that CIJA has videos. Engels confirmed there are around 400,000.

Schulz asked if there are video or audio recordings linked to this process. Engels said no. Audio is not possible to obtain. Material is from early and open sources. The reason video and audio are collected is because they are taken down and have metadata.

Schulz asked if there are videos or audio records linked to Raslan. Engels said that there is no documentation with Raslan’s name or videos with metadata linked to him.

Schulz asked if CIJA has facial recognition technology. Engels said no.

Kroker asked if one can contact the witnesses. Engels said yes, CIJA wants to keep up with contacts so that they get contacts’ approval before publishing information.

Kroker asked if witnesses are in Syria. Engels said that in general, the majority are in Syria or neighbouring countries, but a few are in Europe. CIJA focuses on the ones inside Syria not in Europe.

Kroker asked if Raslan contacted CIJA directly or through insiders. Engels said that he had no knowledge of this.

The Court Monitor could not hear Kroker’s question, but Engels stated that all regime apparatuses coordinated the oppression. A checkpoint belonged to one apparatus, but the people who worked at the checkpoint were from another apparatus. At the beginning, one problem was that a person could be detained by one apparatus/location, but then released from another.

Kroker’s next two questions were unclear, but Engels noted January 18, 2018 and Branch 251.

Kerber said that Engels mentioned that he had documents for the court to add to the minutes.

Schuster asked if the PowerPoint presentation would be included, too. Engels explained the documents that he brought, including the presentation.

Böcker quoted a report and asked Engels if it pertained to Branch 251. Engels confirmed and noted that the Branch was responsible for some checkpoints in Damascus and that it is difficult to disconnect Section 40 with Branch 251 because the section is a division of the Branch.

Böcker asked if more defectors were described in the report than just one. Engels read from the report that “eight defectors from GID were described.”

The witness was dismissed.

Kerber said that the trial of Eyad will be separated on February 17, 2021. A final verdict for him will be announced on February 24, 2021. The timeline could change because of COVID-19. Starting January 2021, the trial will be moved to the building of the Higher Regional Court. The room is being built to maintain the COVID-19 distancing instructions, but has fewer seats for the public. For important sessions, the proceedings will be held in the current courtroom.

The proceedings were adjourned at 12:20 PM. The next trial will be November 19, 2020 at 9:30AM.

Trial Day 45 – November 19, 2020

Bodenstein appeared for Fratzki and Wessler appeared for Reiger. The witness entered the courtroom with her attorney Dr. Kroker.

The proceedings began at 9:30AM. There were six spectators and three individuals from the media present.

Testimony of P19.

P19 is a 43-year-old female journalist from Damascus who was called by Dr. Kroker. She is unrelated to the accused by blood or marriage.

Judge Kerber’s Questioning

Kerber asked P19 to talk about her background, her detention, and how she came into conflict with the regime.

P19 was raised in Damascus. She attended preparatory and secondary school, then studied mathematics and informatics at Damascus University. Before the revolution, she was a math teacher. Previously, she was not associated with the regime because the status quo in Syria was to be fearful and Syrians were not able to say anything. Her family was especially cautious because, when P19 was 10-years-old and in fourth grade, her father told her about an incident involving the regime. P19 told the story to her friends who then told their families. Afterward, the security forces came to school. They summoned her father and after that, her family was cautious. However, with the start of the revolution, she thought about being non-biased, not with the regime, not with the opposition. When the incidents started in Dar’a and two people were killed on the first day, she decided to be against the regime. She knew her stance would put her in a difficult position because she could get detained or die. She did not think that she would leave Syria. She was detained for participating in demonstrations several times. The first time was during a demonstration in Damascus in November 2011. The second time was on February 4, 2012 when she was taken to Al-Khatib Branch, then she was transferred to the General Intelligence Services. She did not remember the exact date of the third time, but it was for one day in 2012. She was also detained later in 2012 for two days. The last time she was detained was on June 9, 2013 and it was for ten months. After that experience, she decided to leave the country.

Kerber said that they were interested in the second detention. Kerber asked P19 to describe her first and second detention.

P19 said that her first detention was after a demonstration. Demonstrations on Fridays had more people than other days. P19 was in Al-Amara العمارة. The first minute [of the demonstration], there was a large number of security forces and they detained many people. Her group of detainees consisted of seven people and there was another bus with detainees [P19 did not know the number of detainees on the second bus]. The reason for her detention was that she and two other women saw security forces beating a small child. The child was around 12 or 13-years-old. P19 and the other women thought that because they were females, the forces would not approach them and they wanted to take the child. The security forces detained the women and the child. Then the forces took them to a police department in Al-Amara where there were members of the Air Force. P19 was there for six hours. The forces wearing military clothes were different from normal police. She and the six others were put on the floor and stepped on. After six hours, they transferred the group to the criminal police for three days and then to a court where she was released on a court decision.

Kerber asked about P19’s detention in February 2012.

P19 said that on February 4, 2012, there was intense shelling by the regime on Homs, especially on Al-Khalediyyeh الخالدية. Her friends who were activists from Homs talked with her and said that there was a high number of injuries and not enough medicine. She had a friend who had another friend who could transport medicine through the Red Crescent if she gathered some. A group of six people, including P19, brought medicine from their homes, bought medicine from pharmacies, and collected medicine. P19 took everything home with her. She arrived home between 11:00PM-12:00AM and started sorting the medicine. Around 1:00AM, there was heavy banging on the door and it was slammed open. More than 20 forces entered the house from the first floor (P19 lived on the second floor and her flat had four rooms next to each other). Wherever P19 looked, she saw forces. Her brother woke up and they took him to their car while he was still in his pyjamas. After that, they searched every small corner of the house for an hour. Then they took P19 and her two sisters in a big car. Her brother was next to the driver while P19 and her sisters were in the back along with a staff member.

Kerber asked if P19 was on a mini-bus. P19 said that in Syria, it is known as a 7-passenger car. Later, P19’s neighbours told her (they were blindfolded) that there were several cars and one was a DShK-mounted one. The forces took them to a place that P19 did not know at the time. She later learned she was at Al-Khatib. They arrived at 3:00AM. P19 stayed there for three days. She was interrogated each of those days. She was then transferred.

Kerber asked P19 if she wanted to talk more, or if she wanted questions. P19 said “as you would like”.

Kerber asked if they were blindfolded. P19 confirmed.

Kerber asked how P19 knew that she was at Al-Khatib and what happened.

P19 said that when she got out of the car, she was blindfolded. She remembered being in a corridor, then the group was separated. She did not know where her siblings were. The forces wanted to search her, but they did not find a woman to do so. They waited about 30 minutes until they could bring a female to perform the search. P19 thought the woman was a nurse from the Red Crescent. When the nurse searched P19 in a room, she asked P19 to take off all her clothes. One of the male personnel opened the door to the room and told the nurse to search P19 well. The nurse closed the door and did not let him in. The nurse also told him that P19 was menstruating. P19 thought the nurse was not nice, but that this was a nice act. After she was searched, P19 was taken to the solitary cell.

Kerber asked if P19’s brother was taken too. P19 said no, just her and her sisters. P19 never saw her brother [in detention]. Usually, they do not put males and females together. The sisters slept and then were taken to interrogation.

Kerber asked about the interrogation. P19 explained that the first day of interrogation was about the medicines and how she acquired them. When the interrogator opened her laptop, he found out that P19 was a member of a political party (“with us, for a democratic Syria” movement / حركة “معنا من أجل سوريا ديمقراطية”). The interrogator’s interest shifted toward the movement. Each of the interrogations were relatively long (2 – 4 hours). The first day, P19 could not see the interrogator because she was blindfolded. The second day, the same interrogator instructed her to remove the blindfold. The third day, P19 was interrogated by a different person who asked her detailed questions. She was unable to hide details because he had her laptop. The interrogator then told P19 that he wanted to take her to another place. Usually, when someone is blindfolded, they can see a bit from the bottom of the blindfold, but she could not because her blindfold was tied tightly. The interrogator was not really interrogating, but rather was accusatory. He said “what have you done to the country? You sabotaged the country. You divided the country”. The interrogator asked P19 why she did not go live with her brother who was in the Emirates (as if he was saying “why don’t you just leave Syria and stop being our problem”). Because the interrogator knew about P19’s siblings, she feared something dangerous would happen to them. The interrogator told P19 that she would be released the following day. But the next day she was transferred to another Branch.

Kerber noted that there were two people present during the interrogation and asked if there were more people there. P19 said that one or two military personnel escorted her to the interrogation and then the interrogator told the military personnel to leave. The door [of the interrogation room] stayed open and there were people passing by.

Kerber asked P19 if she was beaten or threatened during the interrogation. P19 said she was not beaten by an interrogator. However, she was beaten (1) in the car when she was taken from her house to the Branch, (2) when she was taken from the solitary cell to interrogation, and (3) when she was taken to the toilet. In any “route,” there was beating. Even when one of the personnel brought her to the interrogation and hit her in front of the interrogator, the interrogator told him not to hit P19. But the personnel hit her again when he returned P19 to her cell after the interrogation.

Kerber asked P19 if she sensed that there was hierarchy between the interrogators. P19 thought that the first interrogator might have been a legal person and that the second one was “responsible” [a colloquial word in Syria to describe a high-ranked/important person. “Responsible” can be equated to “official”].

Kerber asked how P19 knew that the second interrogator was an officer. P19 said that a staff member told her that she was going to see an officer.

Kerber asked P19 if she saw the officer. P said no. The blindfold was tied tightly.

Kerber asked if P19 recognized the interrogator’s dialect. P19 thought the interrogator was a Kurd, but she was just assuming because his dialect was from the eastern area. In Syria, people usually speak a “white dialect” (joint dialect). However, he had some words he spoke that made her feel that he was a Kurd. What confirmed her feeling was that he asked her about a Kurdish oppositionist who was famous to Kurds and to oppositionists. He asked P19 about the Kurdish oppositionist with a kind tone - not as though he hated the person, so P19 felt that he was a Kurd.

Kerber asked P19 to describe the general conditions in detention, such as the cell, the food, etc. P19 said that on the first day, she and her sisters were in a narrow cell (1.4 meter or 2 meters).

Kerber asked if there were three people in the cell. P19 confirmed. After the interrogation, she was in a cell alone. In the solitary cell, there were two beds and blankets that smelled. P19 knocked on the cell door and told the staff member that it is impossible for one to bare these conditions. He replied that she should manage that herself [i.e., it was her problem to deal with].

Kerber asked about the size of the cell. P19 said that it was approximately the same size as the room where she was put with the others—it was 1x2 meters. There was a corridor and toilets near the cells. The toilets were in bad condition. Regarding food, there was enough but it was not good. Bulgur with red broth. Dinner was a loaf of bread with potato.

Kerber asked how many times food was served. P19 said three times, but she did not eat in the morning.

Kerber asked about liquids and water. P19 said that they were allowed to go to the toilet three times. She drank when she went there.

Kerber asked if P19 heard sounds of torture or screams. P19 said that the corridor between the solitary cell and the toilets or the interrogation room was where the staff members were because that was where they used to sleep. It was also the place where they tortured detainees. The sounds of torture were heard all the time, except at night. It started in the morning at 5:00AM, then was all the time. Usually, the sounds were from more than one person being tortured at the same time. In the corridor near the toilets, detainees being tortured were always in the squatting position.

Kerber asked if P19 meant in the corridor or in the cells. P19 meant the corridor near the entrance to the toilet. She had to pass through the detainees. What drew her attention was that their ages were between 18 – 25 years-old. One time, security forces were torturing someone. She could hear the detainee’s voice but then it vanished suddenly. On the same day when P19 went to the toilet, there were traces of blood. She didn’t know if the blood belonged to him, or if he passed out or died. But she knew that his voice/sound stopped.

Kerber asked about the condition of the detainees who were in the corridor (nutritional state, bruises, etc.). P19 said that they were wearing shorts. They appeared exhausted and had signs of beating. They were shaved bald.

Kerber asked about the signs [of torture]. P19 said that there were no signs of beating with cables/whips, but there were bruises. She noted that the space was dark; they were all in a basement, so it was hard to differentiate details. However, what drew her attention was that the detainees stayed in the corridor for 4 days.

Kerber asked what happened after that. P19 said that her sisters were released on the third day because they did not do anything wrong. The second interrogator told P19 that she would be released. They took her in a van in which she was the only female and the rest were young men. P19 thought they were going to take her home or at least away from the Branch, but she found herself in another Branch: the general intelligence. She stayed there for 21 days. During the first 15 days, no one asked her a question. After that, they interrogated her like before. Then she was referred to the military jurisdiction and to the civilian jurisdiction. The day before she was released, she was taken to a civilian prison. In the morning, she was presented before the judge and was released.

Kerber asked if P19 identified anyone at the court. P said no.

Kerber asked P19 to look to her right and if P19 recognized one of the accused. P19 said no.

Kerber asked whether P19 saw the accused in the Branch. P19 said that she did not see him in the Branch. She saw a “white” person who was wearing glasses.

Judge Weidner’s Questioning

Wiedner asked if P19’s first detention was in November 2011. P19 confirmed.

Wiedner asked if it was because of the demonstration in which she participated. P19 confirmed.

Wiedner asked around when P19 started to participate in demonstrations. P19 began to demonstrate around July.

Wiedner asked how the regime reacted to the demonstrations. P19 said that the demonstrators used to organize “flying demonstrations مظاهرات طيارة” [demonstrations that abruptly began and didn’t last for long, usually 5 – 10 minutes]. When they planned the demonstrations (P19 became one of the demonstration planners), their purpose was to annoy the security forces. They did not want the government to think that nothing was happening in Damascus. They wanted to convey that the demonstrators were active. P19 clarified that she was talking about the centre of Damascus: Al-Midan الميدان, Al-Amara العمارة, and in sensitive locations like Al-Jisr Al-Abyad الجسر الأبيض where the Makhlouf Branch is located. At most of the demonstrations, the security forces came in the middle and pursued the demonstrators. It was like a marathon. The ones who were captured were detained. There was a funeral in Al-Midan and there was shooting. P19 was injured in her hand/arm [same word] by a [hunting rifle]. At a funeral in Al-Qadam القدم, there was shooting. If the security forces captured someone, they beat the person a lot. In general, they were more violent with young men than with girls. In further away locations (closer to the rural areas/countryside), the detentions were violent and the shooting was violent. P19 participated in demonstrations in Barzeh برزة and Qudsayya قدسيا in 2011. In Barzeh, several people died.

Wiedner asked what time P19 was referring to. P19 said June 2011 to 2012 when most of the demonstrations took place. She remembered a demonstration in Barzeh. She was in the demonstration and saw that they detained people in a violent way. She went back home after the demonstration, only to find out that the security forces / pro-regime media filmed other places in the area to make it look like people were living normally and the birds were chirping [they filmed a calm/peaceful area and showed it on TV to make it look like nothing was wrong].

Wiedner asked if there was live shooting on the demonstrators. P19 said that in the center of Damascus, there was no direct shooting except with “metallic balls” [referring to the ammunition of BB guns خردق]. There were shootings in Al-Qadam and rural Damascus.

Wiedner recalled P19’s comment about how someone died at a funeral. P19 said the death happened in Al-Qadam. It was a strange funeral. The demonstrators wanted to hold the funeral in Al-Midan because the person who died was killed at a demonstration in Al-Midan. The security forces wanted his corpse (as a way to prevent the funeral from happening), but his family refused. His friends decided to hold the funeral in Al-Qadam. P19 looked behind her and saw that one of the forces [عنصر] fired. A demonstrator was injured in his leg, but she fled. Back then, the forces used gas or smoke bombs.

Wiedner asked if the forces wore uniforms. P19 said that they were not ordinary police. She assumed that they were security forces because they wore military clothes (like the ones stationed at the checkpoints). They used to chase the demonstrators.

Wiedner referred to P19’s first detention and asked if torture happened. P19 said that among her group were two girls with criminal charges. They were tortured, as well as the young men. There were always sounds of torture. P19 went to around 5 Branches and there was always torture.

Wiedner recalled P19’s statement to the police in March 2019 that “after they were tortured, the detainees had to step on water. There were always sounds of torture. The men were brought back to the cells and they were not able to walk”. P19 confirmed the statement. She did not know why the prison guards instructed the detainees to step on water. Later, she learned that they were tortured by Falaqa and the prison guards made the detainees step on water so that the detainees did not suffer. A female detainee with P19 said that she also stepped on water after Falaqa so the pain does not increase. In the Criminal Security Branch, torture did not happen in the corridors. It was in the interrogation rooms. This surprised P19 who thought that the Criminal Security Branch was [better], but it was actually bad [torture also happened there].

Wiedner asked if it was correct that P19 was not beaten during her interrogation in Al-Khatib Branch – only on the way to the interrogator. P19 confirmed. The interrogators’ treatment was better than she expected, especially because she could not lie because they had her laptop and email.

Wiedner asked if there were signs of beating on her body when she was taken to the interrogation room. P19 said that she had clothes on, so even if there were signs, the interrogator would not be able to see them. Neither Falaqa nor Doulab [tyre] were used on her. She was beaten with the prison guard’s hand or with a stick. He hit her hard on her head. Twice when P19 went to interrogation, there was someone who deliberately came close to her. He did not grab her from her hand/arm, but from [her waist]. Although there were many people, he always came next to her. P19’s sister said the same thing.

Wiedner asked if there were insults or verbal abuse of a sexual nature. P19 could not remember if she was called by her name once. [The least offensive term she was called] was “who**”. There were always insults, like “your mother…”, “your sister…”, “I’ll do this with you…”. Even when they detained her and her siblings and then took them to the car, the security forces talked to P19’s brother about his sisters in an [inappropriate way], like “you are taking your sister to sleep with the rebels!?”

Wiedner asked if P19 was threatened sexually. P19 confirmed. The forces said “I’ll do this with you, or your mother, or your sister…”. She was explicitly threatened with rape in all of the Branches.

Wiedner asked if P19 was threated or insulted [during interrogation]. P19 said the second time, after the interrogator told the guard عنصر not to hit her, the guard told her to “confess, otherwise you don’t know what will happen to you.” (This was the same person who got close to her in the corridor).

Wiedner asked if she took that seriously. P19 said yes, she was uncomfortable.

***

[15-minute break]

***

Wiedner asked how P19 knew she was in Al-Khatib Branch. P19 learned her location for certain later. But when she and her sister entered the Branch, her sister (who was a lawyer) told her that they were most probably in Al-Khatib. Also, when she was transferred to the other Branch, there was a girl who told P19 that most of the girls in Al-Khatib were transferred to the general intelligence directorate. When P19 was released, her sister confirmed that they were in Al-Khatib.

Wiedner asked how P19 knew the second Branch was Branch 285. P19 said that a girl there told her that she was in Branch 285. She suddenly remembered something regarding the court’s earlier question about how she knew that the forces who shut down demonstrations were from the intelligence services. P19 explained that on one of the 21 days when she was in the general intelligence directorate, there was a heightened alert in the Branch because P19’s cell had a window that overlooked a big square. There was a gathering of armed forces. P19 saw them leave the Branch. When she was released, she learned there was a demonstration in Al-Mazzeh المزةthat day.

Wiedner asked if P19 was talking about Branch 285. P19 confirmed.

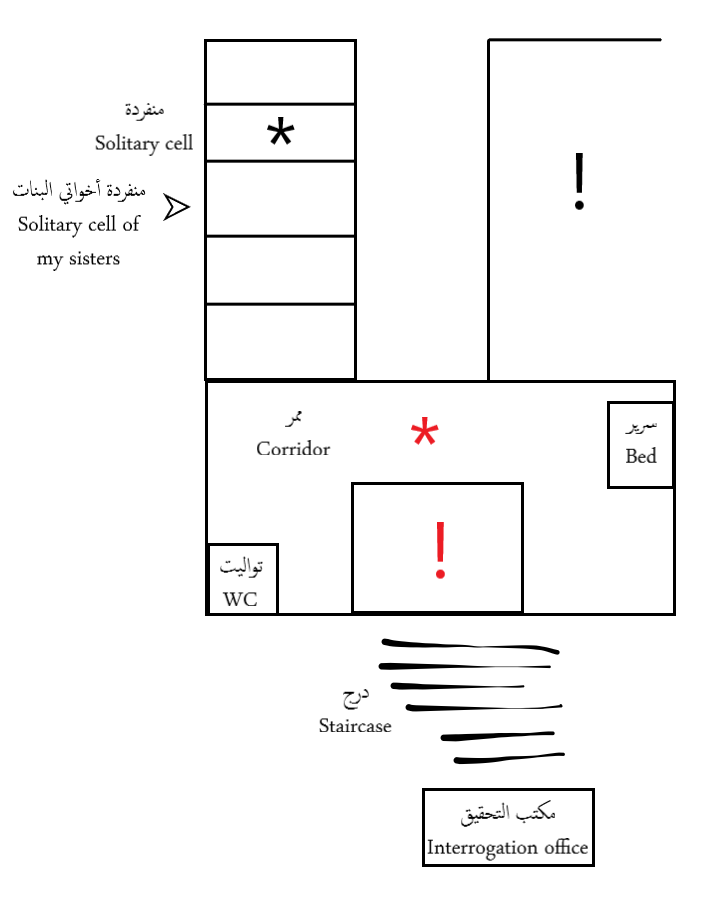

Wiedner recalled P19’s statement that she was in a solitary cell in Al-Khatib Branch. He asked about the size of the cell. P19 said 2x1 meters.

Wiedner asked where the interrogation was conducted and if it was on the same floor [as her cell]. P19 said that she had to go up one flight of stairs, walk through a small corridor, then upstairs.

Wiedner asked if she went up one or two floors. P19 said one.

Wiedner asked if she was interrogated in the same room. P19 confirmed.

Wiedner recalled P19’s statement earlier that she heard detainees scream from torture. He asked if she could tell where [the screams] came from. P19 said that as far as she remembers, the solitary cells were “here” and “here” was a hall and there was one downstairs. The torture was in this place [P described by using her hands].

Wiedner asked if P19 meant the basement. P said yes, in the same place where she was.

Kerber showed a sketch on the screen.

P19 said that there were many solitary cells. The three of them were together, then P19 was transferred to [marked with black*]. At [marked with red!] were the members/personnel and the detainees. P19 was once going to the toilet and her blindfold was not tied well, then she saw a picture of Hafez Al-Assad حافظ الأسد. [marked with red*] is the corridor where she saw the signs of blood [of the man whose voice went away when he was beaten]. She thought [marked with black!] was the men’s cell, but she did not see it because she and her sisters were the only girls in the Branch. At least, she did not hear voices of other girls, but it had been seven years since she was detained, so she mentioned that this might not be accurate.

Wiedner recalled P19’s statement that she heard screams. P19 pointed to the corridor where the screams came from, then pointed to where the detainees were naked [marked with red!].

Wiedner asked if the sounds of torture could be heard in the staircase or the interrogation room. P19 confirmed she could hear the sounds when she was in the interrogation room.

Wiedner asked if she heard the sounds during the interrogation and if the door of the interrogation room was open. P said yes.

Wiedner said that P19 mentioned a man during the police questioning and that his voice (which was coming from the basement) vanished. P19 said the voice was clearly close to her in the corridor.

Wiedner said that during police questioning in March 2019, P19 was asked about that person. Wiedner asked if P19 remembered what she answered. P19 said that his voice just vanished. Maybe he fainted, died or was taken to another place.

Wiedner reiterated that P19 only heard that [sound]. P19 confirmed.

Wiedner asked where she saw the traces of blood. P19 said in the corridor on the floor and maybe on the wall. But she did not know if the blood was old or recent. It was dark and she was blindfolded. She only saw the floor and up to the knees of the prison guard.

Wiedner asked if she was talking about the basement. P19 confirmed.

Wiedner asked if P19 saw corpses. P19 said not in that Branch, but she did in the general intelligence directorate and in the Air Force Branch. In the general intelligence directorate in 2012, she was on the first floor but the men’s cell was in the basement (she thought). The windows were usually open when there is an incident. One time, the windows were open. Four personnel carried a dead body on a blanket. P19 was struck by how they carried the corpse but talked about a totally different topic. As they walked downstairs, the corpse’s head knocked against each step. It was as if they weren’t carrying a human being. The corpse showed signs of torture and was thin. She could see because the place was lit and it was during the day. It was clear that the person died from torture.

Wiedner asked if this incident occurred during her first or second detention in Branch 285. P19 thought it happened during her second detention because she was in the Air Force Branch and was transferred. But it definitely happened in the general intelligence directorate. Wiedner noted that P19 gave the same answer during police questioning.

Wiedner asked if this could have happened in 2013. P19 said maybe. She was transferred there twice: one time from Al-Khatib to the general intelligence directorate and another time from the Air Force Branch to the general intelligence directorate.

Wiedner asked if P19 remembered whether there was torture in Branch 285 during her first detention. P19 explained that her cell was far from the other detainees. It was closer to where detainees handed over their belongings [when they arrived]. When the forces brought new detainees, they beat people at a “welcome party” before they even took the detainees belongings. She could hear the sound of people’s heads being hit against the wall of her cell.

Wiedner said that P19 mentioned more methods of torture in Branch 285. P19 said the “welcome party.” In the corridor near where she was interrogated, there were people being interrogated. They were tortured by beatings and Falaqa. When P19 was in the interrogation room in Branch 285, someone was tortured so he would mention a specific thing. The interrogator told him: “say that you raped Alawite women.” The person told the interrogator: “I raped nine.” The interrogator told him: “no, say four.” It was clear that people were tortured to confess something they did or did not do.

Wiedner asked if there was air or windows in Al-Khatib Branch. P19 did not remember windows, but there was air. In general, the conditions were bad, including the health care. She did not get sick, but she asked for a painkiller. [She did not say whether they gave her the painkiller.] When P19 asked for sanitary napkins, they told her to manage her situation.

Wiedner recalled how P19 described the clothes of personnel during her second detention in February 2012. P19 said that some of the personnel were in full military clothes and some were wearing normal t-shirts and military pants. But almost all of them were heavily armed.

Wiedner asked if she was taken directly to Al-Khatib. P19 confirmed.

Wiedner asked P19 to look to her right and if she remembered one of the accused. P19 said that she remembered, but not from the Branch. [Eyad laughed]. P19 said his appearance was familiar. Maybe she saw him somewhere other than the Branch.

Wiedner asked if P19 could specify where she saw the accused. P19 couldn’t because many forces came to her house, and in the Branch, she only saw the interrogator in the dark.

Prosecutor Polz’s Questioning

Polz recalled P19’s statement that there was a young person in her first detention, then asked if P19 knew why he was beaten. P19 thought he was with her at the demonstration, but she wasn’t sure if he actually participated. Demonstrations often started near the mosque, so among the demonstrators were people praying.

Polz asked if P19 thought the boy was armed. She said no. They were in a working-class area with a market and a mosque. In Damascus, there are many checkpoints. If he was armed, he would have been killed, not beaten. Also, at that time, the demonstrations were peaceful and people were careful to avoid violence with the police.

Polz asked if P19 knew what happened to the child. P19 said no.

Polz recalled P19’s statement that the intelligence services came to her house and detained her and her siblings. Polz asked if P19 knew to which Branch the forces belonged. She didn’t know then that specific Branches wore specific uniforms, but she was sure they were intelligence services.

Polz asked P19 how she categorized Al-Khatib (e.g., if it belongs to the general intelligence services). She thought [it belongs] to the general intelligence services since direct transfers take place there.

Polz apologized in advance. He asked P19 if she was a victim of sexual abuse in Al-Khatib. P19 said that she was not raped, but faced verbal abuse of a sexual nature and was harassed. Her breasts were touched deliberately. She was searched by a female, but when a male opened the door, he saw her naked (the man who opened the door was not the same man who took her interrogations – she saw the first man, not the second).

Polz said that P19’s sisters were released, then asked about her brother. P19 clarified that all of them were released after two days.

Polz asked if P19’s brother was tortured in Al-Khatib. P19 said no. She understood that the focus was on her. Her brother did not tell P19 details, but the torture was only at the “welcome party” and when he was on the way to interrogation. “It was not torture torture” [i.e., not ‘real torture’]. Her siblings were interrogated and it was clear from the beginning that they had nothing to do with the medicine. P19 was careful to say that the medicine was for her and for the political party.

Polz recalled P19’s statement that men were treated differently than women by the forces at demonstrations in Damascus. Polz asked if the treatment was different in Al-Khatib, too. P19 said that nobody was treated politely, but they were harsher with men. For example, women were detained and brought to the bus, whereas for men, 5 – 6 people would beat one male detainee who could die between their hands. Even in the Branch, they tortured men more. Maybe it had something to do with numbers. In the Air Force Branch, there were around 50 girls, but maybe 100,000 men (estimate). Men were always accused more often of carrying weapons. That did not mean that women did not get tortured. But in comparison, men were tortured more often.

Polz asked if P19 knew about the divisions in Al-Jisr Al-Abyad or Hafez Makhlouf حافظ مخلوف. P19 said that there was another Branch that belonged to Al-Khatib (or they were related to each other). It was called Hafez Makhlouf Branch, and he was its head.

Polz asked if P19 had more knowledge about it. P19 said that one of her colleagues was detained there for two months and was tortured. When he was released, he died. He was a champion bodybuilder in Syria.

Polz wanted to confirm that P19’s colleague was the body builder, not Makhlouf. P19 confirmed.

Polz asked if that division/Branch was in Al-Jisr Al-Abyad in Damascus. P19 said yes.

Linke asked if the interrogations in Syria were conducted like in Germany. P19 explained that there was always a signature, but nobody could see what they were signing.

Linke asked when P19 had to sign documents. She said that she signed something (she didn’t know what it was) when the interrogation ended and she was transferred. She also signed a blank paper in the general intelligence services.

Plaintiffs’ Counsel Questioning