How to Document Atrocities in the Gaza War

With the attention of the world fixed on the current Israeli siege and bombardment of Gaza, SJAC has chosen to use this space to provide resources that can assist efforts to document violations of international humanitarian law and support any future accountability processes. Since 7 October, when Hamas militants killed more than 1,400 Israelis—many of them civilians—indiscriminate Israeli airstrikes have killed more than 8,300 Palestinians and displaced more than a million people (most of whom are children). Israel has denied almost all humanitarian aid from entering Gaza in this period of time, most critically the fuel necessary to sustain hospitals and bakeries. There have been contradictory accounts of some of the atrocities that the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) and Hamas have apparently committed in this most recent cycle of violence, which, as the UN Secretary-General notes, comes after decades of Israeli occupation and apartheid rule over Palestinian territory.

Most notable among the disputed events is an explosion on 17 October that, following multiple IDF evacuation warnings, killed hundreds of Palestinians sheltering at the al-Ahli Hospital in Gaza City. Hamas and the IDF both put forward contradictory explanations for the cause of the hospital explosion. Although the US and other western governments quickly endorsed the IDF account, ongoing open-source investigations by major media outlets have called into question key elements of that account. Independent open-source intelligence analysts online have likewise disagreed in their explanations. With regard to the al-Ahli explosion and other apparent atrocities resulting in civilian casualties, large volumes of potentially useful open-source documentation have circulated—but often without being identified, preserved, and verified in ways that could support future accountability processes. The intermittent blackouts that Israel has imposed on Gaza as of 27 October, apparently by targeting its telecommunications networks, will only make it harder to document what UN officials have described as clear war crimes.

Such kinds of issues are familiar to SJAC from its experience documenting humanitarian law and human rights violations in the Syrian conflict. Disinformation has been a hallmark of the Syrian conflict, and social media companies have gradually removed the Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube posts that once constituted a publicly-accessible archive of alleged war crimes. It was partly due to such developments that SJAC developed Open-Source Resources that human rights organizations and media activists can use to easily identify, preserve, and verify open-source documentation; other similar kinds of guides are also available online. In the wake of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, SJAC pointed to the Syrian experience in anticipation of the war crimes that Russian forces would soon commit in a new theater of conflict. Tragically, the Syrian experience is again relevant as the world witnesses Israel impose the kind of siege and collective punishment that the Syrian government pursued against civilian populations in cities such as Aleppo.

Below are some of the guide’s key methodological recommendations and free online resources for working with open-source documentation which are designed for use by both individuals and organizations. These resources do not, of course, guarantee that national or international justice mechanisms will choose to rely on such documentation to hold perpetrators accountable. At the very least, however, these resources can support such accountability efforts if and when the political will materializes.

Documentation and Preservation

Preserving open-source content is particularly important due to the potential for this content to disappear without prior notice and for a variety of reasons—whether because the original user who uploaded the content deletes it or because the hosting platform removes the content on the grounds that it violates terms of use. Below are the key steps for preserving open-source documentation and properly cataloging it, a process of archiving necessary to complete before proceeding with the investigation workflow:

1) Identify the nature of the content that needs to be preserved: images, videos, written documents, etc.

2) Collect the information needed to archive the content properly and facilitate future database searches, such as the content title, description, category, and file type.

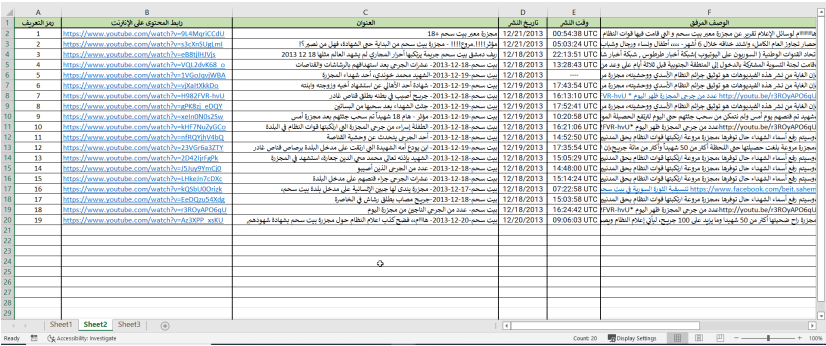

Database example (Excel file):

3) Keep at least three copies of each stored content, including the original version and at least one backup copy stored in a separate geographical location to ensure data retrieval in case of technical failure or natural disaster.

4) When saving open source content and documenting it, specify descriptive data including the source identifier or the person who uploaded the data online, the content's link on the internet, the content's title, publishing date, and any descriptive information that can be obtained from the content itself, such as capture date, geographic location, file size, duration (if it's a video or audio).

5) It is essential to document and record how the archived content was obtained, processed, and all the operations performed on it (the chain of custody) to enhance the value and credibility of the archived content as evidence.

Below are several online tools to help you in your documentation and preservation work:

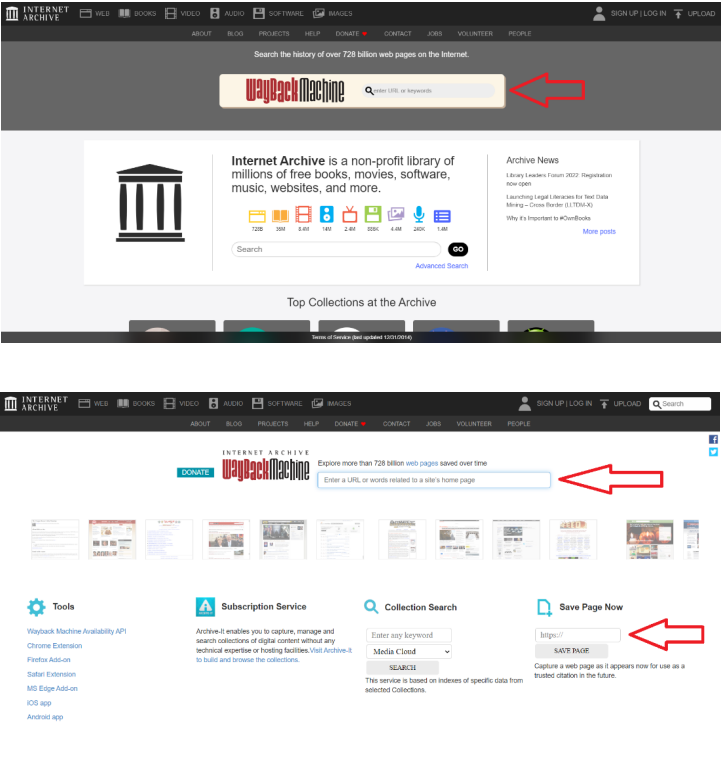

archive.org: A free, public digital library that provides access to a wide range of valuable content and allows the public to download and upload digital materials to and from its databases. The majority of its data is collected automatically using its web crawlers, which work to preserve as much publicly available content on the internet as possible. Its web archive, known as the Wayback Machine, holds more than 728 billion web pages, with more content continuously being added. A tutorial in Arabic can be found here.

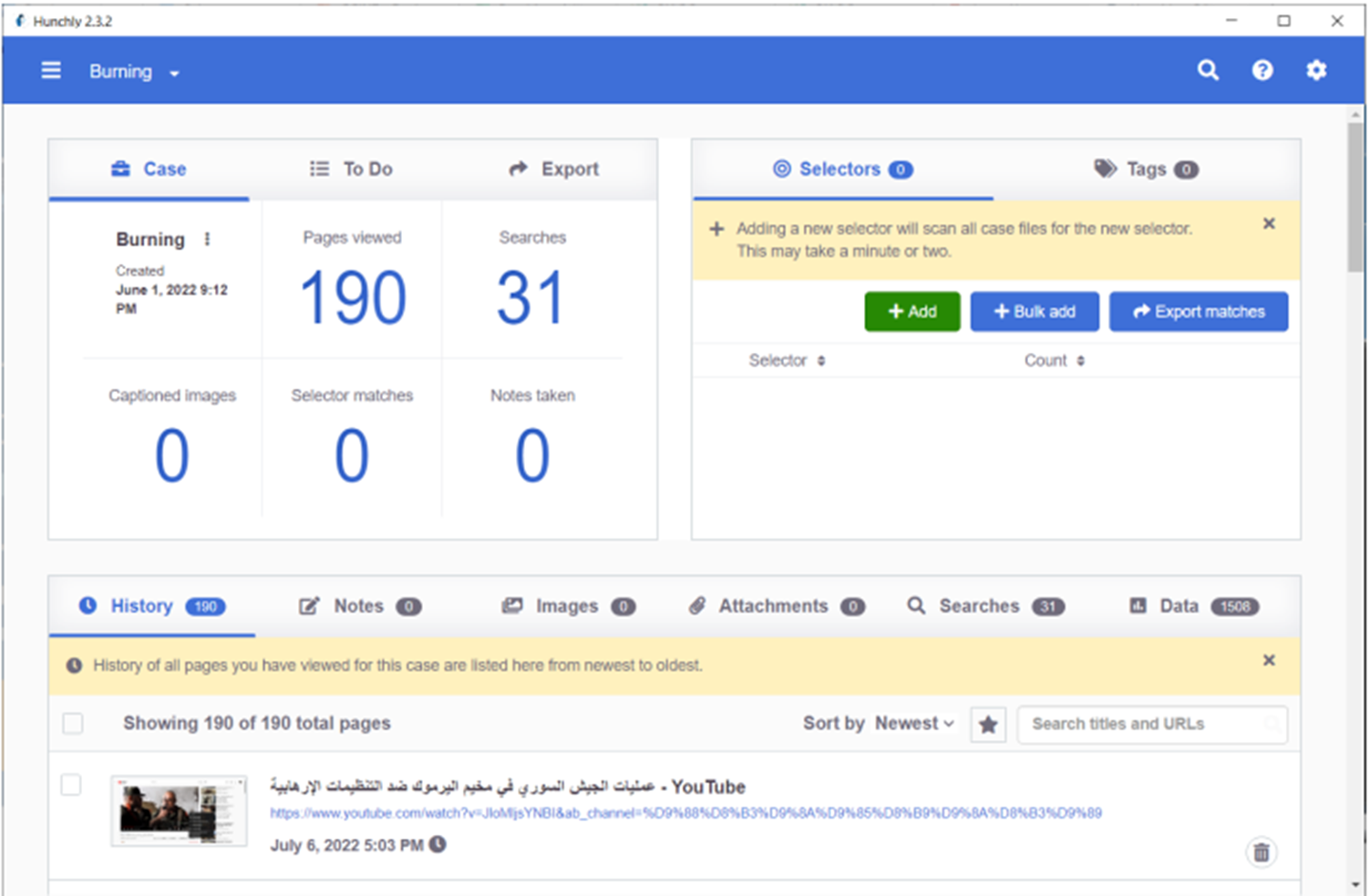

Hunchly: A web scraping tool designed specifically for online investigations. Its extension operates within the web browser and automatically captures and documents every website you visit, adding explanatory comments to them, in addition to many other capabilities.

Confier: A web archiving service that creates an interactive copy of any web page you visit, including the content that appears through your interactions with web pages, such as playing videos, audio, scrolling, clicking on buttons, and so on. This service retains the data it archives on its own online service providers, and it allows users to create a free account with 5 GB of storage space.

Bayanat: For larger organizations that have collected a significant amount of documentation, this relational database can take the place of the other tools in cataloging documentation and performing analysis. SJAC can provide training on the use of Bayanat to interested organizations.

Verification

Before using any information as evidence, it must undergo a verification process to confirm its accuracy and reliability. In general, you should ask the same questions every time you try to verify information; and doing so, where possible, consult independent technical experts, local entities such as activists and human rights defenders, or members of your own investigative team.

- Content Origin: Is the content original? How did we obtain the content? Has it been previously published on the internet? When did it first appear?

- Data Source: Who uploaded it to the internet? Is the account that uploaded it known and with a consistent online presence, or did it only recently appear? Has the identity of the account been verified?

- Date and time of the event depicted: Is there descriptive data (“meta-data”)? What was the weather like, and is it consistent throughout the entirety of the content? Do the shadows match the claimed time?

- Location where the content was captured: Is there descriptive data? What visual evidence can help identify the location?

- Any other evidence that supports what the content portrays: Is there information from any outside source that can corroborate the content?

Below are some online tools to help you verify content:

1. Reverse Image Search:

Most search engines offer reverse image search, and some search engines provide better results based on geographic locations or by offering additional features during the search process. For example, Yandex and Bing allow you to make modifications to the image you are reverse searching, while Google does not offer this feature.

2. Reverse Video Search:

You can search for a video by using multiple screen captures of the content and conducting a reverse image search. Our Training Guide (found in our Open-Source Resources) includes tips on how to best capture video frames and screenshots for use in a reverse video search.

One possible tool: InVID and WeVerify plug-in that facilitates both reverse image search and reverse video search

3. Geolocation

When working with open-source materials, it's common to come across content that was captured in one location but presented as if it happened somewhere else. Such content may include meta-data that contains geolocation information useful for determining the place where the content was captured. However, most social media companies delete meta-data upon uploading content to their platforms in an attempt to protect user privacy. Moreover, even if meta-data is available, there is a chance that it has been fabricated. Therefore, you should try to independently analyze each piece of open-source content and verify the location where it was captured using geolocation techniques. This may involve referencing geotags, unique landmarks, place names, street signs, and more; and comparing them with satellite imagery to accurately identify the location where the content was captured.

Tools used in the process of geolocation include:

A. Wikimapia

D. MapAction

E. Google Maps and Google Earth Pro: You can download KML and KMZ files as extensions for Google Earth, enabling researchers to combine the capabilities of various tools such as Wikimapia and OpenStreetMap with Google Earth and use them within the same program.

Here is an example of how the above methods and tools were used to geolocate barrel bomb attacks in the Syrian conflict.

4. Date and Time

There are many methods and tools that can assist in determining the date and time when a photo or video was taken, including the content’s descriptive data, reverse image, reverse video search, satellite images (if you can obtain two consecutive images of the same location before and after the event, you can estimate the time more accurately), and other clues in the content detailed in the Training Guide included in our Open-Source Resources.

You may also want to estimate time using shadows visible in the content. There are tools like Suncalc that can determine time based on shadows (a tutorial in Arabic can be found here). To estimate time using shadows, you must have basic information about the geographical location where the content was captured and the date of capture. Critically, you also need to obtain an image taken from an ideal angle where the shadow appears vertically on the original object, where you can use a tool (such as: https://eleif.net/photo_measure.html) to measure the dimensions in the image.

However, sometimes you may not be able to obtain a suitable image to use this method for time estimation. In such cases, it's preferable to use Shadow Calculator, which provides a simulation of the shape, length, and direction of the shadow throughout the day, allowing you to draw its shape and track its changes with time.

___________________________

For more information or to provide feedback, please contact SJAC at [email protected] and follow us on Facebook and Twitter. Subscribe to SJAC’s newsletter for updates on our work.